This newsletter was originally published on our Substack. Read and subscribe here.

Since the appointment of three Trump-nominated judges to the Supreme Court, the American public has endured a string of devastating SCOTUS decisions affecting everything from reproductive justice to voting and immigration rights to queer and trans rights. Environmental protections have also been under attack, from West Virginia vs. EPA (limiting federal agencies’ ability to restrict carbon emissions) to Sackett vs. EPA (undermining the Clean Water Act).

The court’s rightwing turn has been historic and alarming. In addition to a trend of more politically motivated rulings, the arrival of Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett has been accompanied by a sharp and politically salient uptick in the Court’s use of the Shadow Docket—an obscure procedural route through the court, which used to be primarily bureaucratic.

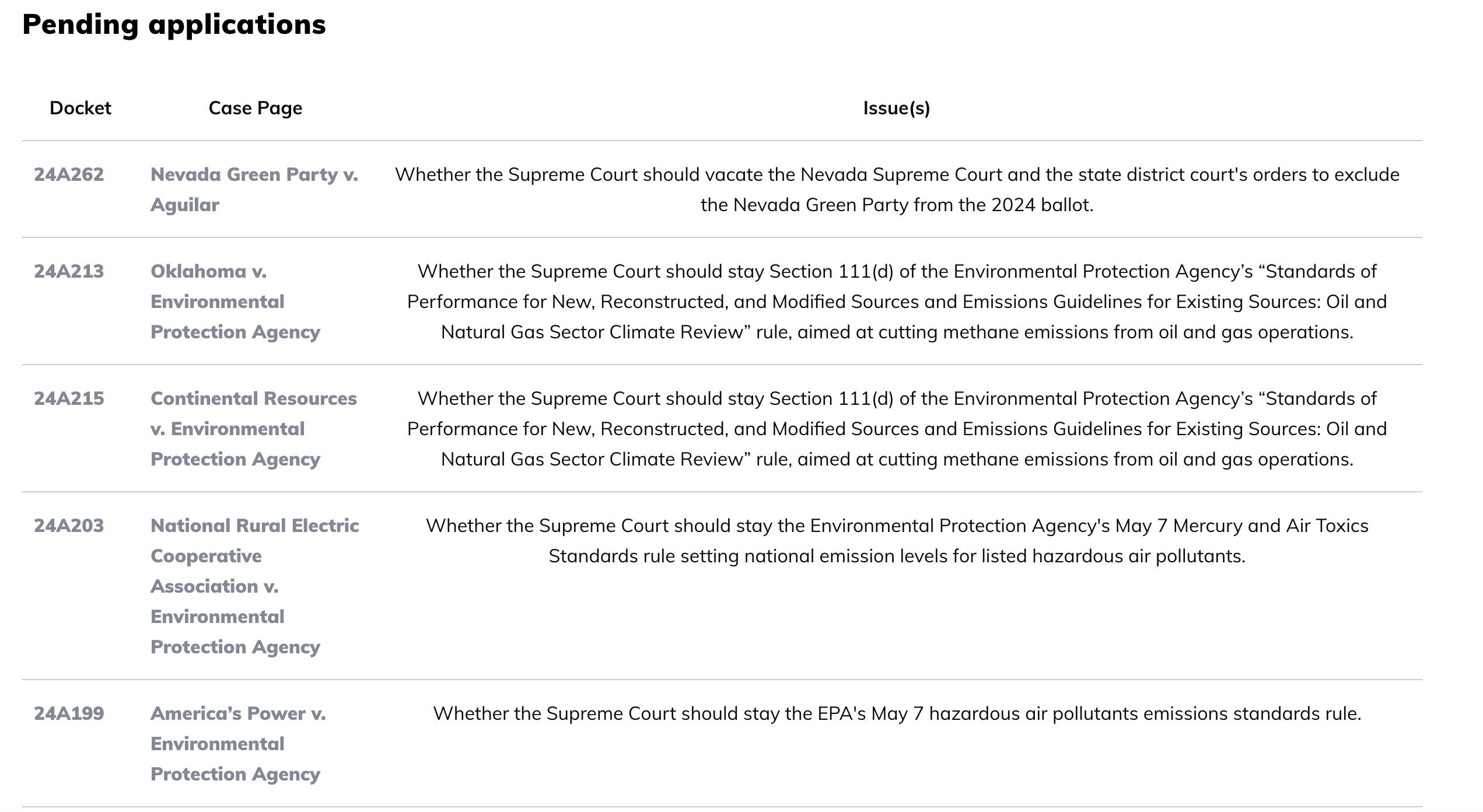

SCOTUS has been using the shadow docket to issue meaningful and conservative decisions interfering in ongoing cases in the lower courts—prompting concerns from more liberal members. And as of this writing, all but one case on the shadow docket is challenging the authority of the Environmental Protection Agency to do its job, threatening a litany of blows to the federal government’s ability to protect the environment and combat climate change.

Reinventing the Shadow Docket, MAGA-Style

Until recently, the ominously named “shadow docket”—also known as the “emergency” or “non-merits” docket—was a relatively obscure procedural tool. When applications are sent to the Supreme Court, they are directed to either the merits docket—for settled cases being appealed—or the shadow docket. The merits docket—which most people think of when we think of Supreme Court cases—requires cases to have moved fully through the lower courts, and requires full briefing and oral arguments before the nine SCOTUS justices, with signed opinions being released after arguments conclude.

By contrast, as a useful Brennan Center explainer notes, shadow docket cases “typically do not receive extensive briefing or a hearing. The decisions are accompanied by little to no explanation and often lack clarity on which justices are in the majority or minority. They are sometimes released in the middle of the night, creating a sense of palace intrigue.”

One particularly concerning use of the shadow docket has to do with cases that have not yet reached final judgment. As James Romoser wrote for SCOTUSblog, “the shadow docket gives litigants a potential shortcut: When a lower court issues a ruling (even a preliminary ruling that does not decide the full case), the losing side can ask the Supreme Court to order an emergency ‘stay’ of that ruling […] By preserving the status quo as it existed before the lower court’s ruling, emergency stays can favor litigants who hope to run out the clock” and in some ways leapfrog the lower courts’ authority.

Historically, the shadow docket was little-used, and not particularly relevant to most of us. That began to change during the Trump administration, with the recent appointments of three right-wing justices. As the Brennan Center writes, “the justices have begun to issue far more rulings, and more significant rulings, through the shadow docket. Today, the justices grant relief in contentious shadow docket cases twice as often as they did just a few years ago” (emphasis added).

The Trump administration’s Justice Department was itself an enthusiastic user of the shadow docket. As NPR reported last year, “in just four years, the Trump Justice Department asked the court for emergency relief an astounding 41 times, and the court actually granted all or part of those requests in 28 of the cases. In short, not only did the Trump administration aggressively seek to use the emergency docket, often leapfrogging over appeals courts entirely, but it succeeded with the tactic.”

Compare that to just eight requests on the shadow docket for the 16-year duration of the Bush and Obama administrations.

At least one Trump-era shadow docket ruling—Louisiana v. American Rivers—has already taken aim at environmental protections. In April 2022, SCOTUS ruled in favor of fossil fuel interests, reinstating a controversial Trump administration rule “preventing states from blocking infrastructure projects that could contaminate rivers, lakes, and streams….without citing evidence or providing an explanation of how the lower court order threatened irreparable harm.”

Now, it’s getting worse.

EPA Under Fire

Today, the controversial shadow docket, having been retooled as a right-wing implement for pushing through salient and politically motivated rulings with minimal public scrutiny, is chock-full of EPA cases, as others have also pointed out. The cases largely challenge EPA powers to regulate hazardous air pollutants, power plant emissions, and other threats to the prospect of halting catastrophic climate change.

This is, to put it mildly, cause for concern.

It indicates a clear intention from conservative states and fossil fuel companies to take aim at environmental protections, weaponizing the conservative majority’s willingness to make controversial rulings that fly in the face of established precedent to push their political agenda.

E&E News has already reported on this trend, noting the Ohio vs. EPA ruling back in June, which “blocked EPA controls on smog-forming pollution that wafts across state lines.” Even Justice Amy Coney Barrett registered concern with this ruling, writing a dissent arguing that “the court reached its decision in the good neighbor case ‘based on an undeveloped theory that is unlikely to succeed on the merits.’”

Environmental advocates are already closely tracking the potential ramifications of the remaining EPA cases on the shadow docket. It’s also important for the wider public to understand the possible harm to environmental protections that the cases represent, and to understand the massive imbalance that this politically motivated use of the court system exacerbates in our political system.

Want more? Check out some of the pieces that we have published or contributed research or thoughts to in the last week:

The Other Group Praised By Ginni Thomas

You Don’t Need To Defend Betting Markets To Defend Polling

David Yost’s Long Crusade Against Immigrants

Democrats Aren’t Sure Which Kamala Harris They’re Going to Get