Progressives have been encouraged by President Biden’s choices of anti-monopoly leadership in Lina Khan, Tim Wu, and (potentially) Jonathan Kanter. But in the interregnum between personnel announcements and actual confirmations, corporations are getting as many transactions done now as possible. And while the Biden Administration seems on the precipice of reining in the power of Big Tech and other monopolists soon, the FTC, one of the two agencies charged with enforcing antitrust law, continues to be hobbled by chronic underfunding.

Since last year, the number of Hart Scott Rodino (HSR) premerger notifications — the program by which corporations alert the FTC and DOJ Antitrust Division they plan to merge — has tripled, with 266 filings this April compared to 79 filings last April. Recent mergers approved by the FTC, like AstraZeneca’s Alexion acquisition, have also encouraged a corporate buying spree. As Matt Stoller wrote, the FTC greenlit the $39 billion merger without a second request for information (meaning the agency took no action to even formally assess possible anticompetitive effects), causing investors to rejoice that “it’s business as usual in the merger world.” Wall Street Journal reporter Charley Grant speculated the AstraZeneca-Alexion merger shows changes in the enforcement “status quo seems unlikely in the near term, as the administration has focused on other priorities.”

Even if the will to stop it exists, the FTC doesn’t have the funding to stop this boom. In fact, it hasn’t had the funding to keep up with a steady uptick in mergers in years. Aside from the recent spike, the total number of premerger filings increased by 80 percent over the last 10 years. In 2010, corporations filed 1166 premerger notifications. By 2019, yearly filings almost doubled to 2089.

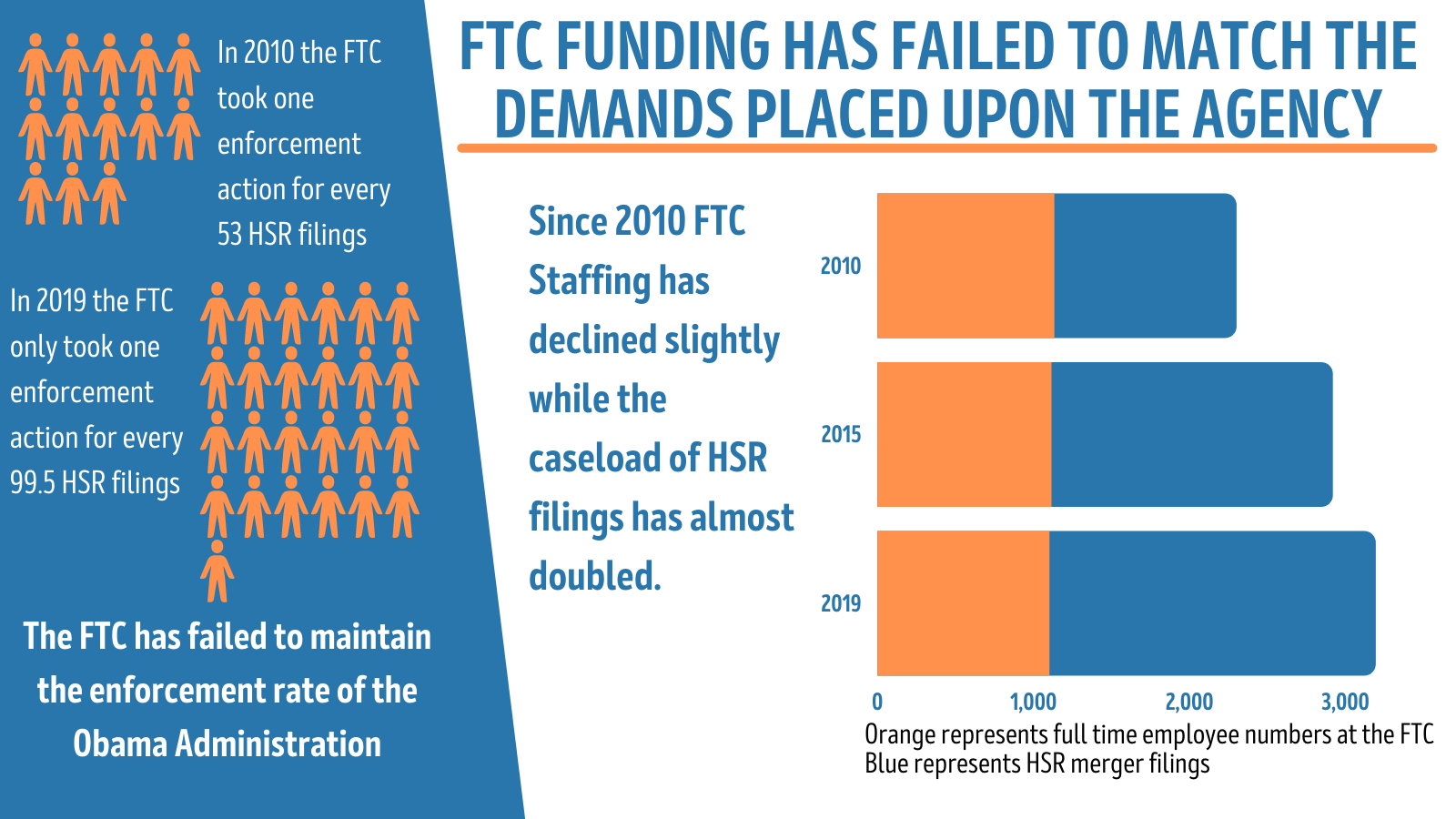

While the number of transactions the FTC is charged with regulating has increased steadily, the number of enforcement actions — challenges to anticompetitive mergers or conduct — has stagnated. A 2020 paper from Equitable Growth showed that while the number of enforcement actions from both the FTC and DOJ hovered at about 40 challenges per year from 2010 to 2019, even as the number of corporations seeking merger approval grew. The FTC’s enforcement actions over the past ten years show the agency hasn’t kept up with increased HSR filings: while FY 2010 saw 22 enforcement actions for 1166 reported mergers, a ratio of approximately one enforcement action for every 53 mergers, FY 2019 saw a mere 21 enforcement actions for 2089 mergers, meaning there was only one FTC enforcement action for every 99 mergers.

Overall funding and staffing levels at the FTC have similarly stagnated. Then-FTC commissioner Rebecca Slaughter said in 2020 that it is an “indisputable” fact that FTC funding has not kept up with market demands; according to Slaughter, the FTC budget has only increased by 13% since 2010 and the employee headcount decreased. This budget increase has not come from increased discretionary appropriations from Congress however, but from a massive increase in merger filings and their accompanying fees. Startlingly, Slaughter notes that “the FTC had roughly 50% more full-time employees at the beginning of the Reagan Administration than it does today.” The situation has become so dire that increased budgets for the enforcement agencies has become a rare bipartisan issue in the Senate.

According to Revolving Door Project’s analysis, FTC appropriations have consistently declined since 2010, when the agency’s discretionary budget authority was $205 million. In the following years the number declined significantly from $205 million in FY 2010 to $180 in FY 2015 and $168 in FY 2019. Accounting for inflation, the decrease between FY 2010 and FY 2019 funding for the FTC amounted to a cut in discretionary appropriations of 30%.

Despite the decrease in discretionary funding, the agency has seen its overall budget increase slightly as a result of the increased merger filing fees that it receives. These are not enough to keep pace with the massive increase in caseload for the agency from which they result. As the fee schedule was implemented in 2001, the filing fees for mergers are far too low to cover the cost of the FTC’s investigations. In a 2021 statement on filing fees, acting Chair Rebecca Kelly Slaughter and Commissioner Rohit Chopra stated that the mega-mergers regulated by the agency “require more resources and staff. For example, large retail or service mergers often require investigation into dozens of geographic markets and large pharmaceutical or industrial mergers often require investigation into a dozen or more product markets.”

The Democratic commissioners specifically identify the need for experts to carry out investigations and litigation, noting “the amount of money the FTC spends on expert costs has risen dramatically over the last several years.” As new technologies are developed, the FTC’s investigations are bound to become more complex, necessitating higher funding altogether for hiring more technologists, economists and other experts. Although the FTC is known for an aversion to costly litigation (a fact which corporations use to their advantage), increased funding would also allow the agency to hire more attorneys to carry out challenges in court.

However, due to declining discretionary funding and fees not keeping up with inflation, the FTC has been forced to expend far fewer resources on each investigation than it had in prior years. The appearance of a budget increase since 2010 needs to be reconciled with the reality that the agency has been crushed under an increased caseload many times larger than the nominal increase in budget.

Our analysis also shows the declining budget coincided with stagnation in the number of full-time employees: from 2010 to 2019, the number of full-time employees of the FTC actually decreased by 31 from 1132 in FY 2010 to 1101 in FY 2019.

Hiring and retaining employees is another struggle for the beleaguered agency as they are forced to compete for attorneys with a private sector that offers ever higher salaries, particularly for young lawyers beginning their careers (oftentimes burdened by significant student loan debt). The FTC’s 2002 Congressional Budget Justification bemoaned the struggles the agency had retaining “human capital” in the competitive labor market. The agency’s struggles were explained to Congress, saying the FTC “currently faces significant competitive pressures from the private sector, particularly for attorneys, economists, and information technology professionals with experience in mergers and Internet-related issues. For example, the compensation for first-year attorneys in the private sector is often three times higher than that available to most Government agencies.” Since the pay associated with FTC employment for attorneys and economists (the GS scale 11 or above) has not increased in keeping with inflation in the ensuing years, one can only assume the agency’s woes have grown since despite the struggles not being voiced so openly by FTC leadership. The lowest GS-11 pay grade in 2002 when adjusted for inflation, is almost 10% higher than the lowest GS-11 pay grade in 2021, a significant decrease in purchasing power for the entry level staff that was already susceptible to the higher wages offered in the private sector in 2002.

So, while HSR filings have been steadily climbing over the past 10 years, the FTC’s ability to regulate these filings has actually decreased because of a decline in agency funding and lack of competitive hiring. Without the resources to handle the increase in merger filings, the FTC has been compelled to reduce the number of enforcement actions it takes, conserving staff resources for only the most important cases. This has resulted in a decline in enforcement actions per merger by nearly half over a short nine year time frame, ultimately benefiting the monopolistic corporations that bolster their power by buying up other companies.

The Biden Administration has made some efforts to better equip the FTC to regulate mergers. The American Rescue Plan allocated $24 million for the FTC to hire more full-time employees “to address unfair or deceptive acts or practices, including those related to the coronavirus.” It’s unclear how much of the funding was allocated to merger enforcement, but in the months that followed the FTC began hiring for Bureau of Competition staff, including attorneys in the Mergers I, Mergers II, Mergers III, Mergers IV, and Technology Enforcement Divisions. These attorneys investigate proposed mergers for anticompetitive effects; more of them means more manpower to take action on mergers that would otherwise pass through the regulators unchallenged.

While the estimate for the FY 2020 and 2021 budgets does provide the agency with marginally more discretionary budgetary authority and staffing, the levels are not sufficient to return the agency to the strength of the early Obama years. But even a return to Obama era levels of funding would not repair the damage done by 40 years of weak antitrust enforcement. As the American Economic Liberties Project argued, economic consolidation has eroded the economy, “undermining the economic liberties of consumers, working people, independent businesses, ordinary investors, and communities.” And if the Biden Administration hopes to rebalance the scales, they will need to not only empower commissioners to pursue aggressive enforcement, but provide the staffing and resources necessary to accomplish such a gargantuan task.