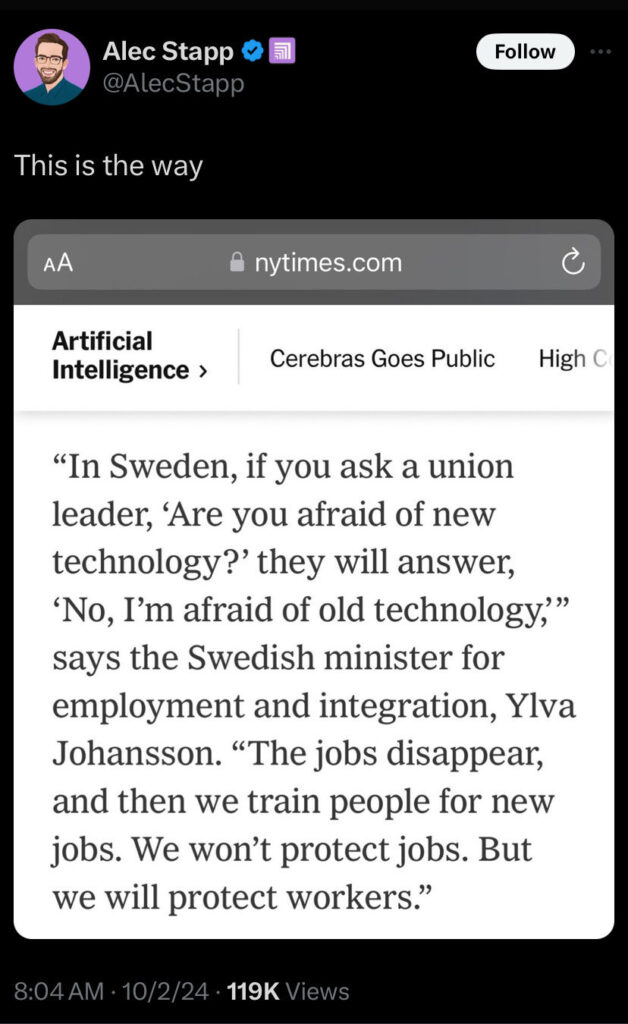

Most of our readers will have heard of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) strike that began Tuesday across East and Gulf Coast ports. This strike has been met by a furor of anti-union takes, originating anywhere from the far right to Democrat-aligned centrists. Some of these takes range from the classic anti-union stance that the union has mafia ties, others pertain to the pay the union president receives, with still others being upset at how much the longshoremen get paid. The most prevalent, though, has been complaints at the ILA’s opposition to the automation of the ports. These claims are enough fodder to fill many articles, so we’re going to focus on the most disingenuous rhetorical move being bandied about by those angry at the ILA, where a pundit will point out that “powerful unions in other countries don’t act this way.” The best example of this? Institute for Progress co-CEO and co-founder posting a quote from a Swedish union leader as a means of attacking American labor organizations.

For those unaware, Institute for Progress (IFP) is a neoliberal think-tank attempting to launder it’s more conservative views with a progressive-sounding name. This strategy is hardly original; both co-founders of IFP previously worked at the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI), a decidedly anti-progressive outfit funded by their corporate friendly parent org The Third Way Foundation (and originally spun out of the Democratic Leadership Council, a corporate funded entity whose “mission was to wrest the Democratic Party away from its left-wing establishment—particularly minority interest groups and labor unions”).

While there, the IFP leadership not only apparently picked up on the PPI’s disingenuous naming conventions as a means to launder their ideas into areas they would otherwise be unwelcome, but they also picked up on the neoliberal economic policies that have undergirded the right wing of the Democratic Party for years. Prominent among those policies is a disdain for the American labor movement that has been the long-term backbone of the party.

This is why Stapp’s use of Sweden as an example of a union culture upon which American labor leaders should base their actions is so ridiculous. This use of the socialist Nordic country’s peculiar labor law is disingenuous, but it is not unique. Conservatives have actually used Sweden’s lack of a minimum wage law as an example to be emulated before as well. After all, upon first glance that sounds like a strong libertarian goal. But this only works when Sweden’s lack of a minimum wage law is presented without any context. This lack of minimum wage is something fiercely protected by labor unions, not a goal of the right. This is because labor organizations in Sweden have so much power that they view a statute defining the minimum wage as a threat – because it could set a lower bound of income that would be below that negotiated by unions, dragging wages down rather than upwards. This does not mean that US labor unions should abandon their longstanding support for a $15 minimum wage and join libertarians and arch conservatives looking to abolish it. Because without the requisite labor power, this would simply undermine wages.

This foundation of strong labor power is also crucial to understanding why Swedish labor unions are more willing to accept automating existing union positions. When Swedish unions can expect employees who lose their jobs to automation to find well-compensated union jobs in another position or employment sector, unions are not as worried about protecting their members’ positions. This is, in part due to the more robust unemployment benefits in Sweden (receiving 80% of pay for the first 200 days followed by 100 days at 70% of pay) compared to the US (where most states offer between 30-50% of pay for approximately 180 days) making the threat of unemployment due to automation far less dire.

But it largely comes down to the issues of union density and coverage. In Sweden 69% of workers are members of a labor union, while in the US that number stands at a mere 10%. This is even more remarkable when it comes to the percent of employers covered by collective bargaining, with 90% of Swedish employees being covered by a collective bargaining agreement compared to 11.2% in the US. The strength of this union membership has allowed Swedish unions to use just the threat of strikes to force employers to capitulate on issues like pay and working conditions.

This does not mean that Swedish unions do not strike. Not only have Swedish longshoremen refused to unload Tesla products in solidarity with workers striking against the electric car company (a practice that is outlawed in the US) this year, but there have been broader strikes in recent years as well.

So with Swedish unions being willing to strike against ports much like their US counterparts, Stapp either appears to not understand Swedish labor, or his principal objection is to US strikers demands regarding automation of the ports. If it is the latter, he should be pushing for the labor protections and welfare state that makes Swedish unions so willing to accept automation, no? It is not as if it’s some secret formula, after all, it’s mentioned at length in the New York Times piece he screenshotted for his tweet:

“In the United States, where most people depend on employers for health insurance, losing a job can trigger a descent to catastrophic depths. It makes workers reluctant to leave jobs to forge potentially more lucrative careers. It makes unions inclined to protect jobs above all else. Yet in Sweden and the rest of Scandinavia, governments provide health care along with free education. They pay generous unemployment benefits, while employers finance extensive job training programs. Unions generally embrace automation as a competitive advantage that makes jobs more secure.”

But Stapp does not advocate for this type of broad welfare state. Nor does he advocate for policies that would enable the union strength that Swedish workers credit with their willingness to accept automation. In fact, he has said he is skeptical of public sector unions, blamed unionization for the decline in journalism jobs, and has stated that he is a neoliberal and that “generally, neoliberals do not like public sector unions at all.” While he claims to make an exception for private sector unions (Sweden’s public sector is 100% covered by collective bargaining agreements), there is little to show for this. Stapp has not mentioned the PRO Act, the flagship labor legislation in Congress, nor has his think tank, the Institute for Progress.

In fact, IFP has received copious funding and has connections to many anti-union groups. This includes one of IFP’s 3 outside board members, Zachary Graves, being the Executive Director of an organization funded by the Koch network with the goal of undermining teacher unions. This same board member also worked with IFP co-CEO Caleb Watney at the R St. Institute, a right wing think-tank that advocated for worker organizations that could be an alternative to traditional labor unions. These alternatives would be very similar to the now-illegal company unions of the gilded age, an intentionally weak organization that cannot stand up to management power. This same, fake-union framework has been advocated by the Mercatus Center, an organization that both co-founders began their careers at and have said they aspire to emulate (but without the libertarian reputation that prevents Mercatus from having influence over the left).

It’s clear that Stapp does not actually wish to reproduce any significant part of the Swedish labor model in the US. He simply finds Swedish labor leaders to be an easy cudgel with which he can bash American labor. Until he starts advocating for the robust labor protections necessary to create a Swedish-style union power, he should refrain from comparing their stances to those of the US labor movement.