If the President hopes to repair the damage of the Trump administration he needs leadership throughout the government he can count on, not only in the White House

On the campaign trail, Biden was reluctant to criticize any aspect of the “Obama-Biden” administration’s record. Since taking office, however, he has made perfectly clear that he is aware of, and has learned from, many of its mistakes. Having watched how an anemic stimulus package in 2009 delivered a slow, faltering recovery and political carnage, the Biden administration chose to go big with its economic response. This initial, consequential departure has earned Biden accolades and prompted a “growing narrative that he’s bolder and bigger-thinking than President Obama” (a narrative Biden reportedly loves).

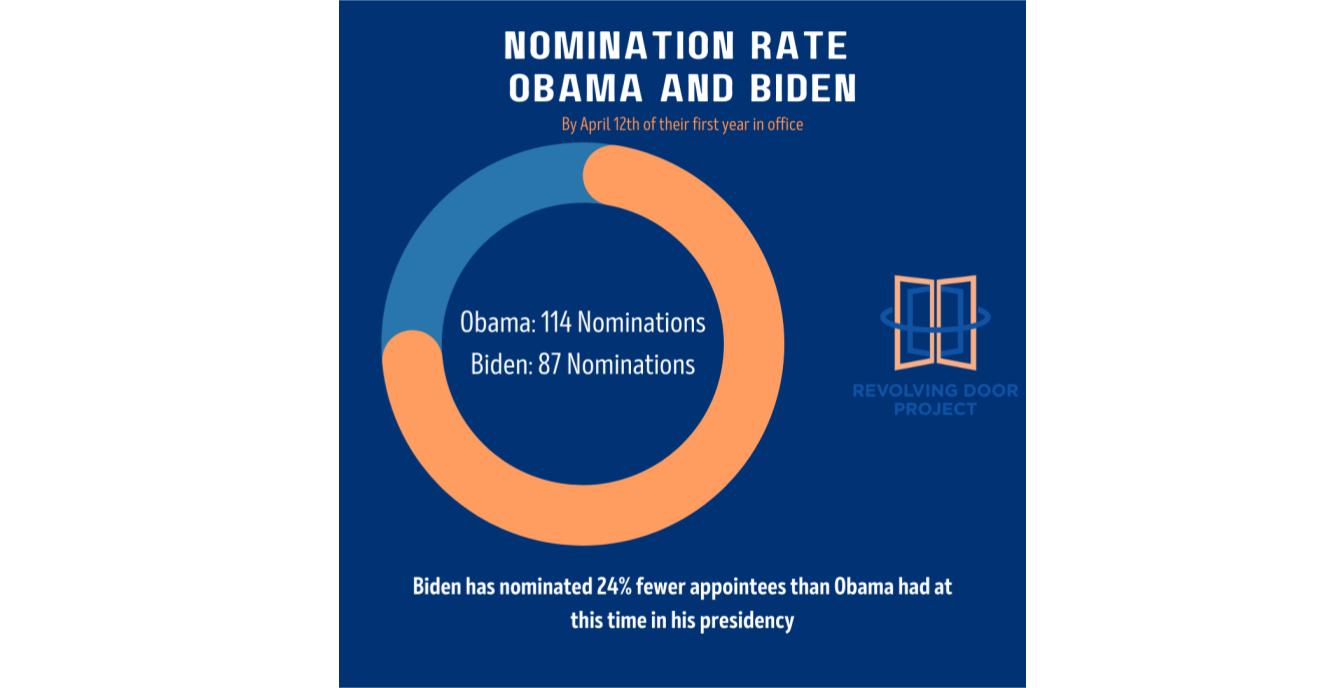

But while Biden may be surpassing Obama legislatively, he is lagging behind him when it comes to the pace of nominations, delaying policy implementation and preventing his administration from reaching its full potential. If Biden hopes to retain the image of a dynamic and bold president, he must pick up the pace of nominations to ensure that every corner of his administration is working to its fullest potential as soon as possible.

Biden is lagging Obama on nominations

On his first day in office, Biden sent nominations to the Senate for most members of his cabinet. As of last month, all but one of them had been confirmed. Nominations for the hundreds of other crucial leadership positions across the government, positions which have significant power to implement policy, have been much slower to materialize. And while the nominations process is regularly sluggish, it’s notable that Biden has not kept up with the Obama administration’s pace, falling behind the 44th president by a significant margin.

Both Obama and Biden were inaugurated on January 20th of a non-leap year. Excluding the nominees who were withdrawn from consideration and duplicates from those who were nominated to subsequent and overlapping positions at the same agency, Obama had nominated 114 executive branch appointees compared to Biden’s 87 by April 12th. The fact that Biden has only nominated 76 percent as many nominees as Obama is surprising considering his administration’s purported desire to offer a stronger and bolder response than the one the Obama administration developed over a decade ago. And while Obama did have a larger Democratic majority in the Senate than Biden does, that fragile hold on power should not prevent the president from presenting nominees to the Senate for eventual approval. The confirmation of nominees is not subject to the same 60 vote threshold required for cloture in the event of a Republican filibuster. As a result, Biden has the ability to bring the Democratic caucus together with his nominees, confirming them with a simple 51 vote majority.

Despite lapses, the Biden administration has taken some commendable, bold actions. Its nominations to the Department of Health and Human Services surpass the level of the Obama administration, a crucial step for tackling the pandemic and other ongoing public health crises. Similarly, Biden has surpassed Obama administration nomination levels for the Department of Transportation, on which Biden will rely to implement his gigantic public infrastructure plan. Finally, he has matched the Obama administration’s number of Department of Labor nominees, who will oversee the agency as it begins rebuilding after being gutted by the Trump administration. But matching the rate of the Obama administration will not be enough if Biden hopes to achieve his goal of being “the strongest labor president you’ve ever had.”

In addition to his work with larger cabinet agencies and departments, President Biden has been proactive in nominating officials to independent agency posts across the government. These are particularly important because, unlike at executive departments, acting officials cannot fill vacancies on multi-member boards. Biden’s three nominations to the USPS Board of Governors are a significant step towards addressing the ongoing crisis there, though he could still take additional actions to ensure that the man who is most responsible for the USPS’ rapid deterioration, Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, is promptly fired and replaced. Biden has also nominated several strong progressives to critical positions at independent agencies, including Rohit Chopra to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Gary Gensler to the Securities and Exchange Commission, Jennifer Abruzzo to be General Counsel to the National Labor Relations Board and Lina Khan to the Federal Trade Commission. These nominations are excellent but insufficient. Currently, the independent agencies of the executive branch have a combined 39 vacant or expired Democratic seats with another 17 nonpartisan seats sitting vacant or expired.

As Biden’s 100th day as President rapidly approaches, it’s clear that he will need to pick up the pace. Ahead of May 1, he should aim to reach or exceed the number Obama had presented by the same day in 2009.

Why this matters

The slow pace of nominations is a persistent, structural problem that predates this administration. Many scholars have long bemoaned our country’s heavy reliance on political appointees (of which there are approximately 4,000), arguing that it makes government far less effective. With so many officials to hire and vet (a process that is even more intensive for the approximately 1,200 Senate-confirmed appointees), presidential transitions are inevitably slow, leaving the federal government in a prolonged state of limbo every four to eight years, with troubling implications for essential government responsibilities like ensuring national security.

Just because this problem predated the Biden administration, however, does not mean that this administration should not do everything in its power to work against it. That is especially true given that need for swift action. The potential cost of stasis is greater than ever.

Biden inherited a significantly weakened federal government. The Trump administration spent its four years in power gutting federal agency workforces, crushing civil service employee morale, and doing everything it could to put politics ahead of effective government. Trump’s war on governance was widespread, its harms encompassing agencies from the Postal Service to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to the Department of Health and Human Services and more. It was also very effective, driving employees out of the government, lowering institutional capacity and preventing science-driven policy. Reorienting agencies and rebuilding lost capacity are urgent tasks and will require bold leadership.

Having political leaders in place across the federal government will also be critical for implementing Biden’s bold policy proposals. Agencies will require leadership outside of the West Wing if they hope to unwind the damage caused by the Trump administration and to start enacting progressive policy.

The State Department will require experienced leadership to repair the international relationships harmed by the Trump administration, and to help Treasury Secretary Yellen implement her global minimum corporate tax. As the Biden budget seeks to restore the institutional capacity and staffing of agencies like the EPA and the Interior Department, he must also provide them with strong leadership from nominees who support his agenda.

Then there are the multi-member independent agency boards, where new political leadership will be especially impactful. At present, vacancies on many of these boards have left them with an equal number of Democrats and Republicans, creating an impasse and limiting the scope of agency action. With new nominations Biden could quickly tip the balance in Democrats’ favor and break the gridlock.

Although these agencies often get less media attention than the large Cabinet level appointments, they wield massive influence over policy. Additional nominations to the USPS board could not only stop mail delays, decreased service, and Amazon union election shenanigans, but also make way for things like postal banking. New nominees to the US Parole Commission, a board with significant influence over criminal justice issues, could have a huge impact on many prisoners’ lives. And a nomination to the Federal Communications Commission could mean expanded broadband access and a tougher hand for telecommunications monopolies.

Biden should act now

The gap in the nomination rate is not permanent and can be remedied quickly if the President and his senior staff wish to make it happen. By the end of his first 100 days, Biden needs to have redoubled his efforts on presenting nominations to the Senate, ensuring that his administration is capable of addressing the challenges before them. Appointed positions hold vast powers over the American government, and if Biden hopes to surpass the accomplishments of the Obama administration, he must at minimum keep pace with the nomination rate of his Democratic predecessor.