Hey Matt!

Glad to hear you’re following the Kroger-Albertsons merger case! But I’m not quite so glad that you’re “considering writing this week about the theory that Kroger executives made a damning admission of ‘price gouging’ when they conceded that they had raised grocery prices by a larger amount than their input costs went up.” Not entirely sure why you’re calling that a theory; it did happen. You can question the implications, but Kroger executives making the admission is a verifiable fact.

Your explanation of why the conclusions being drawn are wrong also has some major issues:

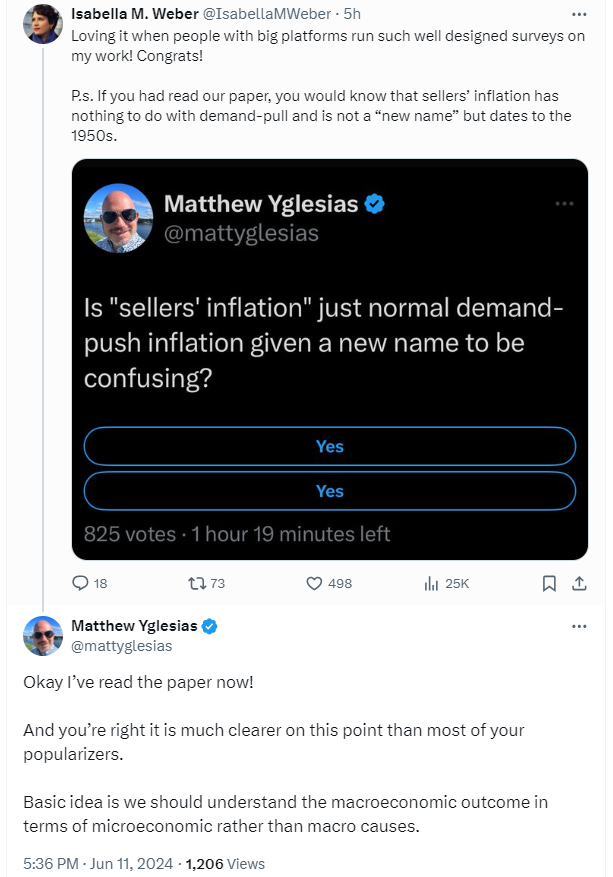

The implication here is that you would expect retail prices to be a pure function of input costs rather than a function of supply and demand. But this doesn’t make sense! Rather than discover a new cause of inflation or a new theory of how it works, leftists have just decided to relabel standard demand-pull inflation as “price gouging.” Of course, people can use words however they want, but as an economic policy argument, this doesn’t get you anywhere.

The idea of relying on the basic supply and demand model from intro macro runs into a wall anytime you have a market of price setters rather than price takers. When outside conditions create an opportunity to raise prices, firms in concentrated markets can jack prices up much more than you would expect from the basic supply-demand chart. This is for a couple of reasons:

- Potential entrants have to overcome significant barriers to enter the market. This is what the second part of your basic function says should happen: seeing high profits, new firms enter, increase supply, and prices come back down.

- As Luke Goldstein mentioned on the Slingshot podcast last week, potential entrants also might know that a big part of those high profits is coming from temporary conditions, so they are deterred from attempting to enter out of uncertainty around whether high prices are ephemeral.

- Not sure if you also took intro micro, but if you did you should know that when an individual firm is setting prices on products with high variable costs, they raise and lower prices frequently to adjust for this. In theory they should do this up and down as variable costs change. What Kroger admitted to was not moving their prices down as variable costs fell. Again, this is a result of concentration; a competitive market should have pressured them into actually following input costs.

- (This is why it makes total sense to have a constant price for a newsletter—which has high fixed costs and fairly low variable costs— while grocery stores constantly shift prices on staple goods like milk and eggs—which have low fixed costs and higher variable costs.)

Also, reupping your old piece “Greedflation is Still Fake” is an interesting choice, since you’ve since admitted that you hadn’t even read the theory you were bashing.

Also, I still don’t think you’ve actually read our take on it, despite seeming to include us as one of those unclear popularizers. Maybe a scorching hot take, but I think we should read things thoroughly before attacking them.

You present these as your main points:

- Greed is a constant in the economy, not a variable, and it doesn’t explain why inflation was so much higher in 2022 than in 2019.

- Price controls and rationing are a reasonable response to certain kinds of supply disruptions associated with war or natural disaster, but if you use them to address run-of-the-mill excess of demand you end up with shortages.

On the first point, I wrote this over a year ago and still have yet to see you or any other pundit averse to sellers’ inflation engage with it:

[Sellers’ inflation] doesn’t really have anything to do with variance in how greedy corporations are. It does rely on corporations being “greedy,” but so do all mainstream economic theories of corporate behavior. Economic models around firm behavior practically always assume companies to be profit maximizing, conduct which can easily be described as greedy. As we’ll see, this is just one of many points in which sellers’ inflation is actually very much aligned with prevailing economic theory.

Essentially, greed is a constant; all firms are profit-seeking. What varies is a justification to raise prices without consumers noticing or objecting. Greed is the motivation that leads to exploiting the opportunity of an inflation smokescreen and pricing power to increase profits.

This isn’t novel; there are whole subfields of economics that are premised on the presumption that how firms, industries, and economies are structured (industrial organization) and contextualized within and alongside other social systems (political economy) change firm behavior away from what Econ 101 would suggest.

As for the second point, I think everyone generally agrees but we don’t concur about what rises to those “certain kinds of supply disruptions.” Personally, I think a complete breakdown of supply chains amid the Covid-19 pandemic, followed by a land war in Europe, followed by significant inflation that was being worsened because of corporations exploiting crises to hike prices and pad profits clears the bar. Especially because the elevated price levels had very limited natural pressure to subside because of the lack of competition described above.

I want to quickly end with what you named as the two big issues with the American Rescue Plan:

“ARP made two errors. One is that it included a bunch of state and local fiscal aid money that was knowably unnecessary given the actual condition of state budgets.”

And:

“The second problem with ARP is that it included a pilot version of the refundable Child Tax Credit that was always meant to become a permanent program and not a temporary stimulus. That’s fine in the spirit of “don’t let a good crisis go to waste,” except it turned out that Joe Manchin had fundamental objections to the idea, which meant it wasn’t a good idea to spend money on it.”

The state and local aid was probably still good. Schools and state governments were scrambling to contain a global pandemic that we were unprepared for. Also, why did you complain that some of it went to paying teachers more? Seems like that’s a good thing. And when you argue that it let GOP governors cut taxes, you cite Texas and Florida, both of which are big states with strong budgets. Did it occur to you that the spending might have been necessary in states with weaker economies? And that the political economy of narrower targeting of aid falls apart in the face of, well, political reality.

And when you complain that the state and local aid “contributed somewhat to inflation,” can you be more specific? Fiscal stimulus seems to have played only a minor role in boosting inflation and this was only one component of ARP.

Let’s close out with the CTC. I think it’s never a waste of money to lift hundreds of thousands of kids out of poverty while making millions less poor. Even if it didn’t stick permanently, it helped millions of people struggling to support their children in an incredibly turbulent moment. And the fact that Joe Manchin blocked extending the CTC is a tragedy, but not a reason to have left it out of ARP.