To rein in monopolies, the antitrust enforcement agencies will require much more than slight increases in funding to restore competition in the U.S. economy.

This newsletter was originally published on our Substack. Read and subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

Budget season is back, and the stakes are higher than ever. Grassroots and progressive groups are once again advocating for robust funding for the agencies that help everyday Americans, and after decades of strained budgets, there’s still plenty of ground for Congress to make up. For fiscal year 2023, Democrats fell short of improving the funding and capacity of many key agencies despite controlling the House, Senate, and White House.

Now, less than two years out from the 2024 election, Biden has yet another chance to prove to Americans that the government can make their lives easier — by using the power of the executive branch to crack down on corporate price-gougers, stop scammers who harm vulnerable Americans, put an end to illegal discrimination at workplaces and homes, and much more. With a divided Congress, Democrats will need to fight tooth and nail to pass a FY 2024 budget that allows agencies to carry out these actions and more. But the truth is, even that budget doesn’t go far enough to fully fund the executive branch to carry out the large-scale enforcement that would restore the public’s faith and support for a strong and fair government.

A prime example is the administration’s antitrust agenda, a key pillar of Biden’s presidency. So far, he has implemented a much-needed, all-of-government approach to reining in corporate monopolies. He’s appointed two trustbusters to lead the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division (DOJ ATR). Two years in, Lina Khan and Jonathan Kanter have made strides to set their agencies back on track after decades of neglect, embracing a spirit of enforcement by taking on anti-competitive monopolies and enacting popular rules that protect consumers from predatory corporations.

But the FTC and the DOJ are still dealing with a deluge of corporate mergers, and still only have capabilities to challenge a handful of those actions each year. Restoring competition in the U.S. economy will require much more than slight increases in funding — these government agencies need monumental budgets to take on entrenched monopolies that have flourished with decades of lax enforcement.

A Long History Of Neglect

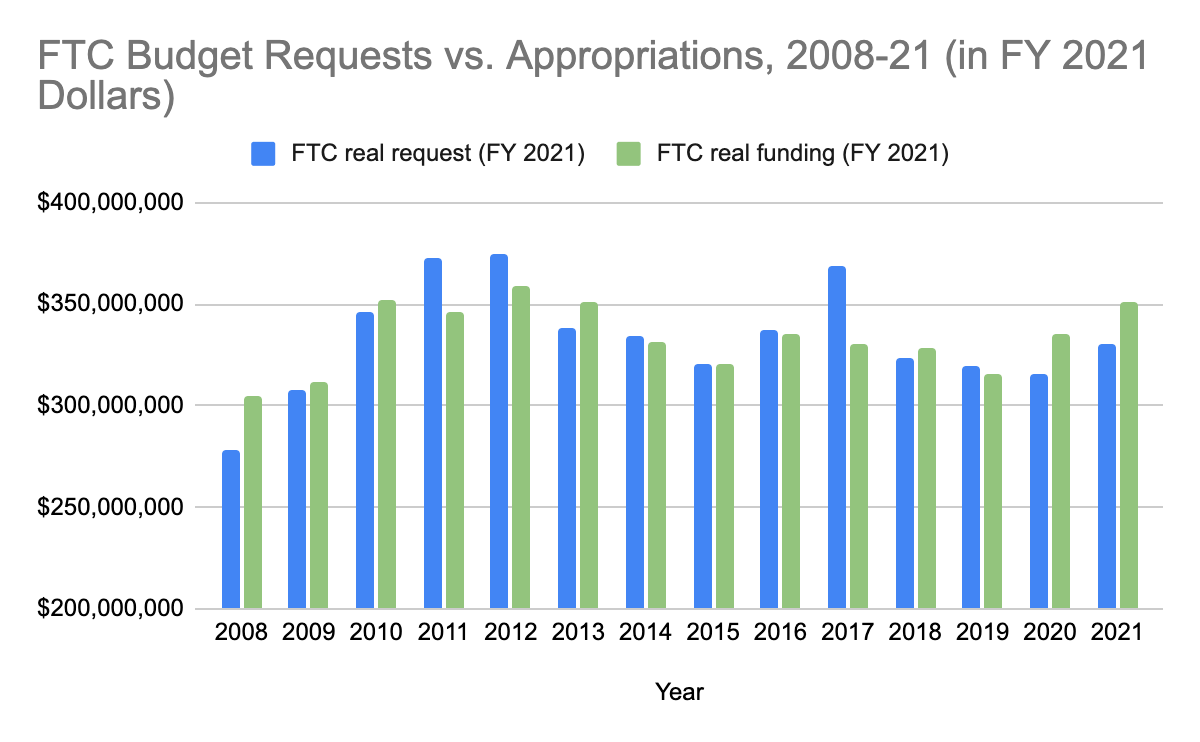

As we pointed out this time last year, the FTC and DOJ ATR are two of the few agencies whose budget requests reflect Biden’s campaign slogan of “Build Back Better,” with increases in funding. The enacted budgets were a step in the right direction, but they still fell well short of agencies’ requests and did not nearly make up for the decade-long stagnation. This year, the FTC and Antitrust Division requested $160 and $100 million increases, along with an additional 310 and 317 employees respectively. These numbers may seem eye popping at first, but it’s important to contextualize these (potential) increases given the austerity that has hamstrung antitrust enforcement.

Since 2010, the budgets for these vital agencies have remained more or less flat when accounting for inflation. When adjusting the Antitrust Division’s budget for fiscal year 2010 to 2022 dollars, the most recent budget represented just a $3 million increase over 12 years. The FTC finally received an inflation-adjusted increase last year, after suffering a similar fate for the past decade.

Over the same period, the workloads of these regulatory agencies have grown significantly. From 2010 to 2022, the number of merger transactions reported under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act (HSR) more than tripled from 1,166 to 3,520. The agencies simply have not had the resources to adequately keep up with these rapidly expanding demands, let alone retroactively investigate anti-competitive mergers that previous administrations approved, such as Facebook’s acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram.

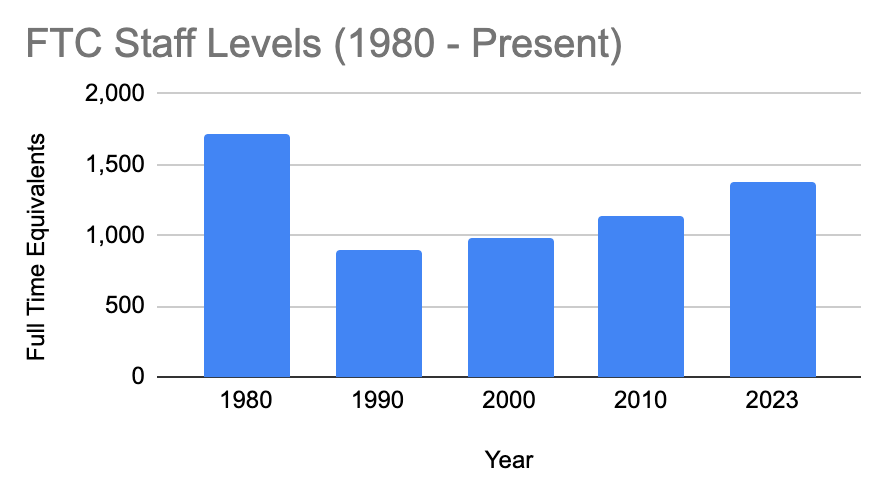

Not only have the budgets stagnated while responsibilities have soared, but the number of employees has also failed to keep up with the agencies’ demands. Comparing the number of employees in FY 1980 — just before Reagan began a 40 year decimation of antitrust capacity and enforcement — to present day employment levels is frankly shocking. In FY 1980, the Antitrust Division had 939 Full Time Equivalents (FTE). Today, that number has fallen by 52 employees. The budget request for FY 2024 would finally increase employment numbers above 1980 levels to a total of 1,204. Meanwhile at the FTC, the number of FTEs has fallen by 339 since 1980, and the budget request for FY 2024 still falls short of that benchmark.

For the last ten-plus years, the FTC and DOJ ATR have seen their workloads triple, while operating with less employees and effectively less funding. These stagnating budgets reflect several interconnected issues. First, FTC and DOJ ATR often fail to request increases in funding that seem to accord with the increase in their workloads. Leadership at these organizations must make the case that their vital roles in consumer protection will be impossible to carry out without adequate funding, rather than accepting the stagnation that has become normalized. Second, there is an inconsistent relationship between agencies’ funding requests and the appropriations they actually receive. As such, while it may be encouraging that FTC and DOJ ATR have requested substantial increases this year, it’s difficult to predict where their funding levels will actually land.

The Biden administration has laudably started to reverse the trend of severely underfunding antitrust agencies — but this year’s numbers are not radical requests that can be chopped down in budget negotiations. In fact, they would be very moderate increases if previous administrations hadn’t dropped the ball. For example, if the Antitrust Division gets the full amount it has requested — which is, as demonstrated by the charts below, far from guaranteed, given historical disconnects between agency requests and actual funding appropriations — it would be a roughly $100 million dollar increase since 2010 when adjusted for inflation. That’s just a $7.7 million increase per year, or 3.4 percent. The FTC yearly increase would be 3.6 percent. In short, the budgets for FY 2024 are merely making up for lost time.

Anti-Monopoly Enforcement And Consumer Protection Makes The Economy Less Perilous For Everyday Americans

More capacity at the antitrust agencies would give the FTC and DOJ the manpower they need to go after both large and small companies engaging in anti-competitive behavior. For more groundbreaking lawsuits like Kanter’s challenge to Google, and the FTC taking on Microsoft, the agencies need adequate staff to move these cases forward.

An important aspect of enforcement that’s been forgotten across the executive branch is the significance of bringing all enforceable cases — even if that results in more cases lost. Take the FTC’s recent action against Meta, the owner of Facebook. The FTC lost their case trying to block Meta from acquiring the virtual reality company Within, arguing that the merger would “stifle competition and dampen innovation” in the VR industry. But as FTC Office of Policy Planning director Elizabeth Wilkins remarked back in February, “having a zero tolerance for risk would not be fulfilling the agency’s obligations to apply the creativity, nimbleness and innovation necessary for this small agency to meet its significant task. More than that, some of the agency’s greatest successes would have never been realized if the agency took a zero-risk approach.”

Wilkins’ comments reflect a principled departure from the risk-averse actions the FTC was once known for pursuing. Americans deserve federal enforcers who have the will (and capacity) to pursue all plausible cases that would preserve a competitive and fair economy. We’ve tried the chickenshit thing for decades now and the result is corporations that account for the occasional enforcement action and any resulting losses as part of their business models, rather than fundamentally altering the anti-competitive ways in which they operate.

On the consumer protection side of the FTC’s mandate, Lina Khan has been directing the agency to amp up its aid to consumers by putting a stop to unfair and deceitful business practices. It is currently in the process of a rulemaking around banning non-compete agreements, a massively popular move that would put power back into the hands of workers. This would affect as many as 60 million Americans per year who are locked into such non-compete agreements by their employers. The FTC followed that up by announcing rulemaking to require companies to provide a “click to cancel” option for consumers seeking to end subscriptions. Any person who has spent hours on the phone with customer service attempting to cancel a subscription (in contrast to the two minutes it takes to sign up) knows the value of the FTC’s action.

These rules, which would collectively impact millions of Americans, were developed by innovative FTC employees seeking to understand how obscure business practices disenfranchise everyday Americans. Undoubtedly, this is the result of the FTC’s concerted effort to recruit employees with expertise in harms posed to Americans by monopolies and deceitful companies beyond the world of law and economics. Increased hiring will mean more creativity in developing these rules within the confines of the FTC’s authority, and everyday Americans will reap the benefits of common-sense regulations that save them time and money.