And House Republicans revive an 1876 rule to cast a pall over civil servants’ job security.

This edition of the Revolving Door Project newsletter was originally published on our Substack. View and subscribe here.

We’ve barely begun wading into the troubled waters of the 118th Congress, and House Republicans are already out for the blood of their longtime nemesis: federal workers.

The first “extraordinary measure” that the Treasury will undertake this month to buy more time before the U.S. hits the debt ceiling (which will happen this week) and can no longer pay for government obligations (which could happen by June) is suspending new investments in the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund, the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund, and the government securities investment fund of the main retirement plan for federal employees, the Thrift Savings Plan, which has over 6 million participants.

Depriving the federal workforce of hard-earned retirement benefits is pretty cruel, but still far from the worst case scenario of what may come if Republicans succeed at forcing the U.S. to default on its debt. Treasury Secretary Yellen warned Speaker McCarthy in a letter last week that “failure to meet the government’s obligations would cause irreparable harm to the U.S. economy, the livelihoods of all Americans, and global financial stability.” Consider this the canary in the coal mine that Republicans have rigged to explode, so to speak, as early as this summer.

Meanwhile, the GOP continues their attempt to return to the 19th century with the inclusion of the Holman rule, first enacted in 1876, in the new House rules package. The Holman rule carves out an exception to standard procedure which allows lawmakers to claw back funds for staffing federal agencies and programs, even if the funds were already included in a given appropriations bill. Lawmakers can even single out individual federal employees for salary cuts.

The Holman rule has been kept alive in various forms over the years, but since the 1880s, new iterations of the rule have generally limited its application. That is, until 2017, when the 115th Congress included a separate order allowing “any provision or amendment that retrenches expenditures by— (1) the reduction of amounts of money in the bill; (2) the reduction of the number and salary of the officers of the United States; or (3) the reduction of the compensation of any person paid out of the Treasury of the United States.” This winter, Republicans included that same language in the new rules for the House.

With the Senate in Democratic control, it’s highly unlikely that Republicans will succeed at passing legislation that zeroes out the salary of any civil servant that stands in the way of their agenda. (Think: climate scientists or public health officials like Fauci, or regulators reining in a bank like Goldman Sachs or a union-busting employer like Amazon.) They also probably won’t get to cut the whole budget for a federal program (like, say, the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division) that they oppose. But we shouldn’t overlook the chilling effect that such a rule can still have. It makes it that much harder for public servants to do their job, knowing that they could earn conservative politicians’ ire, when those same politicians have the power to reduce their salary to $1. The Senate can’t prevent any of the absurd oversight investigations House Republicans are likely to conduct. We hope this isn’t an early indicator that they’ll use their power to bully individual civil servants.

We’d like to think it doesn’t bear saying that Democrats in Congress should not give an inch to the people pushing for the rule’s use. No matter how challenging future negotiations over appropriations are, the Holman rule should not be on the table. Civil servants cannot be a bargaining chip in partisan fights. There is no telling how many good fights would go unfought in anticipation of such a personalized attack.

Federal Aviation Regulation by Former Airline Execs

After last week’s breakdown of the Federal Aviation Administration’s NOTAM system caused a massive grounding of all flights taking off from US airports last Wednesday, the FAA and Pete Buttigieg—to whom the agency reports—have faced heightened scrutiny. As my colleague Dylan wrote for The American Prospect earlier this week, one part deserving of more attention is the personnel choices made about who should oversee the FAA. For more than a year, Buttigieg and Biden chose to keep Steve Dickson, a Trump appointee, in charge.

Dickson was a former Delta executive who was reportedly involved in suppressing a whistleblower’s safety concerns. As we’ve pointed out time and time again, all Trump appointees ought to be replaced as soon as legally possible. As FAA Administrator, Dickson nominally had a five year term, but served at the pleasure of the president. So where does Buttigieg come in?

Well, presidents typically defer to cabinet secretaries when picking who holds technical jobs within their own departments, like the person in charge of coordinating air traffic control, an extremely important responsibility but one which your typical elected leader rightfully knows nothing about. Sure, Biden could pick someone to head the FAA on his own. However, that would be quite a departure from the norm of giving cabinet secretaries significant discretion over how to run their departments. In theory, the cabinet secretary is supposed to know their field well enough to know who is suited to these kinds of complex tasks. So thank goodness we have someone as immersed in the nuances of transportation policy as…uh…the former mayor of Indiana’s fourth largest city.

So Buttigieg and Biden kept Dickson at the helm, until he suddenly resigned last spring. Since then, the FAA has been run by Nolen, despite the fact that by statute, the acting administrator would have been Bradley Mims. That points to an affirmative choice made to pick Nolen over Mims. What’s the biggest difference between the two? Nolen was also a former airline executive (and worked for the industry’s lobbying arm).

The point Dylan makes is that while the NOTAM system failure is not Buttigieg’s fault, the personnel in place and the tone set with the airlines is. Part of the issue is apparently airlines not paying into updating the NOTAM system. Why would they, when Buttigieg will take responsibility and corporations won’t face any serious pushback from the FAA?

Beyond Science

Last week we spotlighted the unusual professional move of crypto-skeptic Rep. Brad Sherman’s former policy advisor, Robert Robilliard, who joined the industry lobby group Crypto Council for Innovation. This week we have another unsavory morsel for you: Wanyoike Kang’ethe has left the Office of Science at the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products to join the regulatory affairs department of Altria, one of the world’s largest tobacco companies, as a top scientist.

You know a company is up to no good when its website prominently features “Moving Beyond X,” when X is their main product, above a court-ordered statement about the deleterious health effects of X. But that’s the case for Altria, whose homepage includes a fancy video montage to the words “Moving Beyond Smoking,” complete with aerial shots of deserts, the ocean, and a shooting star like that Adam McKay sketch about Chevron advertisements.

Indeed, if only BP, which similarly once attempted to rebrand itself as “Beyond Petroleum,” had to include a court-ordered statement on its website about the side effects of its product on the health of our planet! Well, if Altria’s case is any indication, they’d still be able to get influential scientists on their payroll, even though Altria has a history of funding scientists in order to sow doubt about the scientific consensus around the impacts of smoking on the human body.

On the topic of things we should stop setting on fire, the internal documents from BP and the other oil majors released by the House Oversight Committee in December are a fascinating read. The documents are from a couple years ago, when they were setting in motion influence campaigns that we see in operation today. Even when you already know what fossil fuel companies are up to, it’s still disarming to see it in their own words.

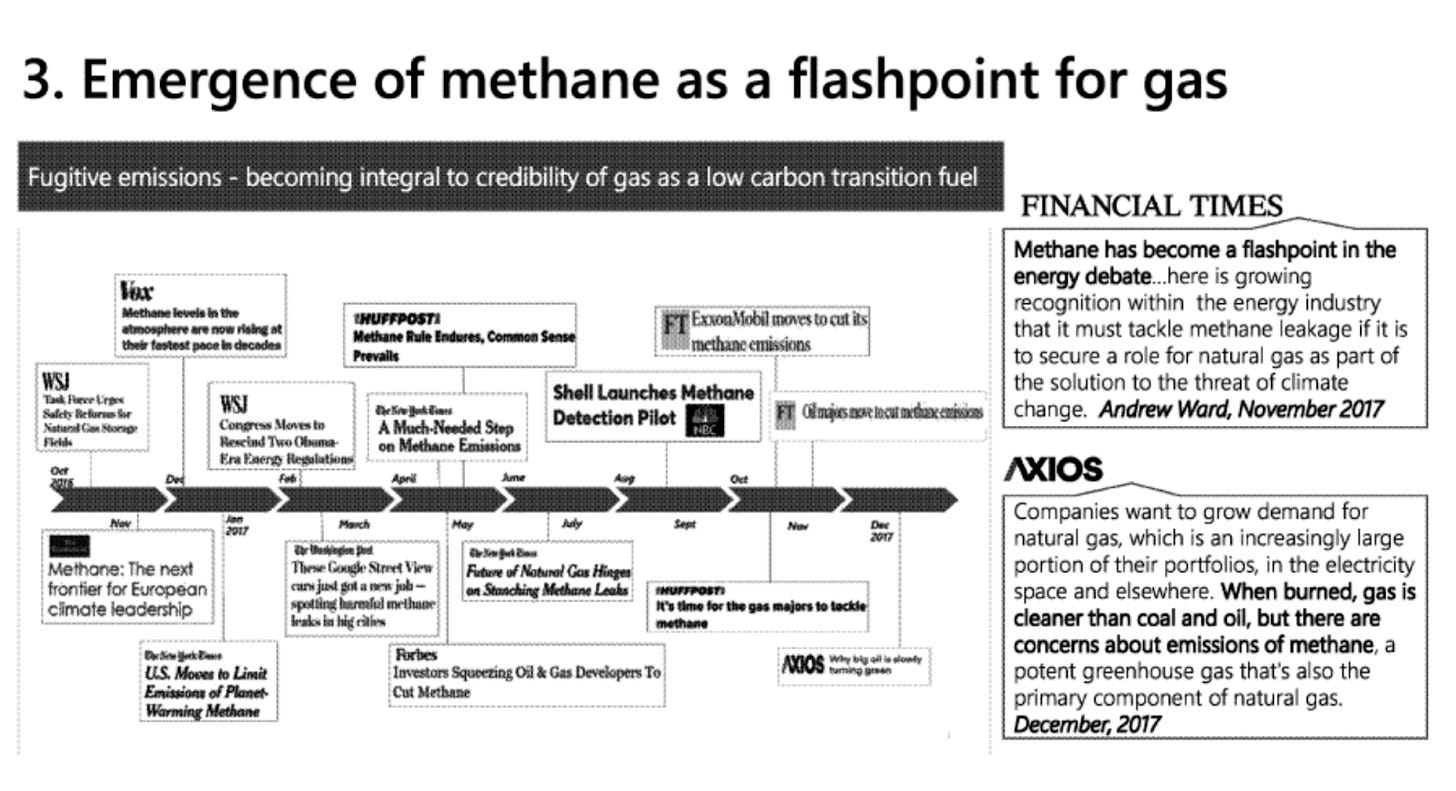

There are some presentation slides on pages 73-75 showing the kind of media stories that give BP nightmares, which includes stories on how gas is still a fossil fuel, like this one in the Financial Times; stories on the dominance of renewables in the future of energy, from the Economist, Stanford and elsewhere; and the emergence of methane as a flashpoint for gas, which stressed them out so much they made this timeline:

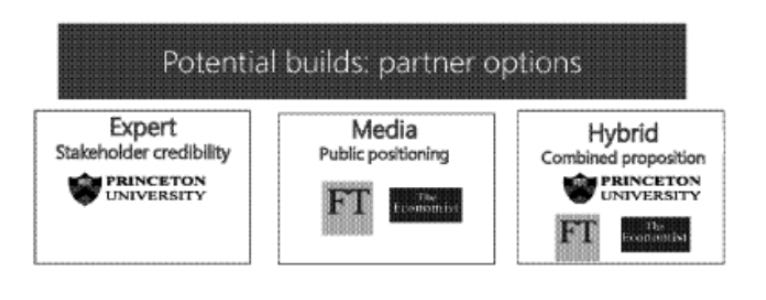

Keep up the pace, journalists! And beware: BP might try to rope you into their plan to “contribute to the debate” and “exploit the positive storytelling potential of existing gas stories” through “agenda-setting IP created in partnership with [a] third party expert as contribution to tackling the challenge.” If, like us, you reread that last sentence three times and still don’t know what it means, it probably means something like feeding top international publications cushy stories based on data from BP partners like Princeton. See explanatory graphic below (from page 83 of the release):

Sell your soul to Big Oil and they’ll even send you to fancy symposiums that function as a “controlled mechanism to engage expert and elite opinion formers in key global hubs” [emphasis added]. Finally, an even worse term than “influencer”! (If perhaps a more honest one.)

The moral of the story is: Don’t do the fossil fuel industry’s PR work for them. They spend more than enough money on greenwashing already.

Thanks to Dylan Gyauch-Lewis for his contributions to this edition.

Want more? Check out some of the pieces that we have published or contributed research or thoughts to in the last week:

What Was Behind Last Week’s FAA Breakdown?

Lax campaign finance rules likely to survive Bankman-Fried scandal

Democrats slough off attacks on Buttigieg