This article initially appeared in The American Prospect on October 27th, and can be viewed here.

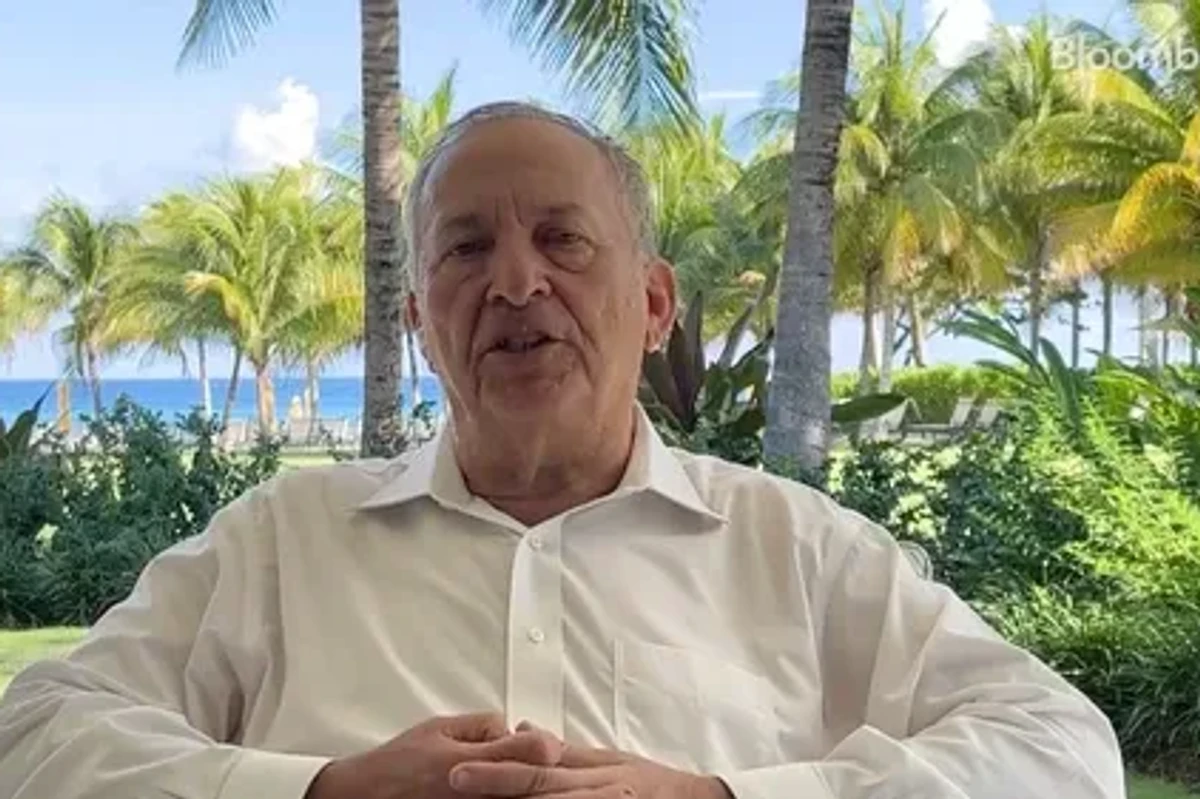

Last week, New York Attorney General Letitia James announced a lawsuit against Digital Currency Group (DCG), its CEO Barry Silbert, and DCG’s bankrupt subsidiary Genesis Global Trading for defrauding investors of more than $1 billion. While the case lacks the lurid details of the FTX collapse late last year, DCG’s alleged fraud has also implicated one of DC’s centrist luminaries: economist and former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers. And much like former FTX CEO Sam Bankman-Fried’s allies in DC, Summers has managed to avoid media scrutiny for his legitimization of DCG.

While Summers became the media’s face of advocating for harsh Fed rate hikes and devastating unemployment, he has spent his time since leaving the federal government cashing in from a litany of advisory positions and seats on corporate boards of directors, in addition to teaching at Harvard. In 2016 he began to advise DCG, holding a position that was alternately called senior advisor and Advisory Board member for over six years, until he resigned from the company in January of this year, after the SEC and DOJ announced a probe into DCG. Afterward, Summers scrubbed his personal website of any mention of his time there. But that does not absolve him of what was grossly irresponsible behavior at a minimum.

It’s unclear when Summers actually left DCG. When his departure was announced in January this year, a spokesperson for Summers claimed that he had actually left months before, but gave no specific timeline or explanation for him continuing to list the position on his website until late 2022. In any case many of the allegations in the NY filings take place while he was known to have been at DCG. But so far there has been little media interest in Summers’ involvement with the company, or, more importantly, his role in making the company appear legitimate.

The seal of approval by respected academics and public officials is often a key part of fraud. Elizabeth Holmes’ Theranos was legitimated by people like Henry Kissinger and future Secretary of Defense James Mattis, and Sam Bankman-Fried relied upon his Stanford law professor parents and Effective Altruism luminaries to legitimize FTX and build relationships with Washington powerbrokers like Bill Clinton. The DCG fraud may not be as exciting as those of Theranos or FTX, but as a venture predicated on a new unregulated securities market (as is all crypto), it too relied on Summers as an established figure in economics and government to help convey legitimacy to investors and policymakers.

The crypto hype cycle that, just one year ago, was able to produce dazzling media spectacles like the “FTX Arena” and “Crypto Bowl” wasn’t sustained by retail investor fear of missing out alone. It took the buy-in of established, influential—and, more importantly, ostensibly neutral—elites like Summers to effectively keep the con going.

DCG’s fraud lawsuit is not the only legal trouble they’ve run into in recent weeks, as the firm refused to comply with an SEC subpoena until ordered to do so by a federal judge. The subpoena reportedly relates to the SEC’s investigation of DCG’s defunct subsidiary, Genesis, over possibly engaging in collusion with the now-bankrupt Three Arrows Capital to exploit the price of a digital asset. Given the host of possible financial crimes DCG and its subsidiaries engaged in, Summers simply cannot be assumed to have been totally insulated from misconduct.

Obviously he should not be presumed guilty, but the media has a duty to ask tough questions of Summers, his history of promoting cryptocurrency, and his role in DCG. Summers may very well have been unaware that the company he spent years in bed with was conducting fraud, but DCG’s ongoing legal problems should invite questions about his judgment. Even if he had no knowledge of any criminal activity, the fact that he implicitly aided in it should cast doubt on his credibility as an economic commentator. What was he doing accepting that position if he had no idea what the business was doing? Was he simply being paid for his prestige and influence without paying any attention to the entity signing the checks?

If he won’t answer these questions, then it might be time for the media to make someone else the most ubiquitous economic pundit in the United States.

Moreover, it isn’t as though Summers happened to join the only fraudulent firm in an otherwise straightlaced industry. The DCG lawsuit is but the latest pebble on a mountain of evidence that fraud within crypto is a feature, not a bug. As we write, Sam Bankman-Fried’s trial is about to enter its fourteenth day of proceedings and what’s been uncovered so far has been quite harrowing. Key developments have included:

- A first look at FTX’s codebase showed that the firm had protocols that both offered unlimited credit to Alameda Research and presented fraudulent insurance fund numbers to its customers.

- Caroline Ellison admitted to considering resigning from her position as CEO of Alameda over concerns over the firm’s (read: SBF’s) use of FTX customer funds.

- FTX and Alameda executives spent $150 million to bribe Chinese officials in order to unfreeze some of Alameda’s assets.

- FTX cofounder Nashid Singh testified to consulting Joe Bankman, SBF’s father, on the structure of a $477 million loan made from FTX to Singh.

- Testimony from Notre Dame Professor Peter Easton found that SBF’s purchase of a $16.4 million Bahamian mansion for his parents was done entirely with investor funds. Similarly, Eaton also identified an instance where at least $493 million of the $551 million FTX invested in the crypto mining firm Genesis Digital Assets (unrelated to DCG’s subsidiary Genesis Global Trading) came from customer funds.

Beyond DCG and FTX, other crypto bigwigs are contending with looming legal battles. Su Zhu, the cofounder of Three Arrows Capital, was apprehended in Singapore in late September; a few days later, the date for Celcius’ ex-CEO Alex Mashinsky criminal fraud trial was officially set for September 17, 2024; and both the SEC and CFTC announced lawsuits against Voyager CEO Stephen Ehrlich two weeks ago.

We also know that Summers understands the basic ethical principle here. In a recent debate with Angus Deaton, he accused his ideological rival, Joseph Stiglitz of a conflict of interest, saying “I do think there is a problem as illustrated by the Joe Stiglitz example I gave earlier, of economists who are hired to take a position.”

The position named here was Stiglitz’ work for the housing giant Fannie Mae analyzing financial deregulation (where he took a position contrary to the one held by Summers). Now, on its face, the critique is absurd. Not only was Stiglitz undoubtedly correct about the dangers of financial deregulation, but it’s hard to see any problem with a government-sponsored enterprising paying an economist for clearly defined professional advice.

But even if we grant Summers’ critique for the sake of argument, surely it is much worse for an economist to be paid on an ongoing basis to be affiliated with an industry whose sole practical use-case appears to be funding crime and Hamas.

Now, Summers attempts to head off this critique by arguing that his policy is “to be hired to present my general views but I will never be hired to advocate on anybody’s behalf.” It was merest coincidence, you see, that he was paid a truckload of money by crypto companies while promoting cryptocurrency over and over. (Incidentally, this second example came after Bankman-Fried’s infamous April 2022 interview on the Odd Lots podcast in which he frankly described the crypto practice of “yield farming” as akin to a Ponzi scheme.)

But Summers’ defense is less than convincing. Not only does his purported covenant with himself lack any means of enforcement, it conflicts with his own brand of neoclassical economics. By the standards of his academic career, individuals are best modeled as self-interested profit-maximizers. Has Summers become a Buddhist without telling anyone? Or has his study of economics elevated him to a higher plane where the principles of economics no longer apply? Given he continues to hold positions outside of his work at Harvard serving on boards and as an advisor to multiple companies, he sure seems to like money a lot. His 2011 financial disclosure showed that he earned $7.7 million in 2010 alone, but that apparently wasn’t enough.

Summers cannot earnestly believe that he and he alone is capable of maintaining impartial economic insight when receiving payment from an outside party, but it provides convenient misdirection away from his accountability for the ventures he has helped promote, including DCG.

Journalists interviewing Summers from here on out have a choice. Will they continue to let him skate on his role in legitimizing DCG, or will they confront him? They must ask probing questions about his involvement with DCG and his convoluted understanding of conflicts of interest. Accepting Summers’ assertion that he is not influenced by corporate ties is a disservice to readers and to the lawmakers who take his economic analysis as gospel.