Last summer, the United States witnessed a devastating breakdown in commercial aviation, with a seemingly endless string of cancellations and delays wreaking havoc on Americans’ summer travel plans. In typical American fashion, the crisis ultimately devolved into the traditional finger pointing and blame shifting. Perhaps the most contentious example of this was the spat between the Department of Transportation (DOT) and airlines, where each blamed the other for the entire mess. In truth, the airlines were largely at fault; their hiring practices had left them sorely understaffed and consequently unable to react to a post-Covid travel surge.

But there certainly was some egg on DOT’s face as well. For starters, they let the airlines get away with these practices. Part of the job of airline regulation involves ensuring good service. Airlines are bound by common carrier obligations, meaning that they are required to offer reliable transit at reasonable rates. If they can’t do that, or it looks like they’re about to get caught with their pants down, DOT is supposed to step in and knock some sense into them.

There was also an argument from prominent trade association Airlines for America that a shortage of Air Traffic Control (ATC) staff was making it impossible for flights to run on time. The DOT quickly pushed back on this, saying that there were enough air traffic controllers to get the job done. But, they quietly ignored the most important part of the industry’s complaint: shortages in a handful of key locations. Airlines use specific airports as hubs, routing lots of flights through those locations to leverage economies of scale. And the argument the airlines had was that those hubs needed more ATC staff.

That nuance illustrates how important robust funding and staffing is for airline regulation; even if general levels of staffing and resources are sufficient, localized shortfalls at airports around the country can have major ripple effects. And overseeing the entire convoluted landscape of ATC and airline operations is a single administration within DOT: the Federal Aviation Administration.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the federal government’s one-stop shop for all things aviation. The FAA oversees air traffic control operations, implements safety regulations on both the engineering and operation of aircraft, regulates airlines’ corporate practices, and enforces consumer protection laws. It is also, by far, the single largest subdivision of the Department of Transportation. It accounts for roughly 80 percent of the total number of DOT employees (some 44,000 out of roughly 54,000). Despite this, the FAA is far from the most well funded administration in DOT, that being the Federal Highway Administration, with a budget more than three times that of the FAA.

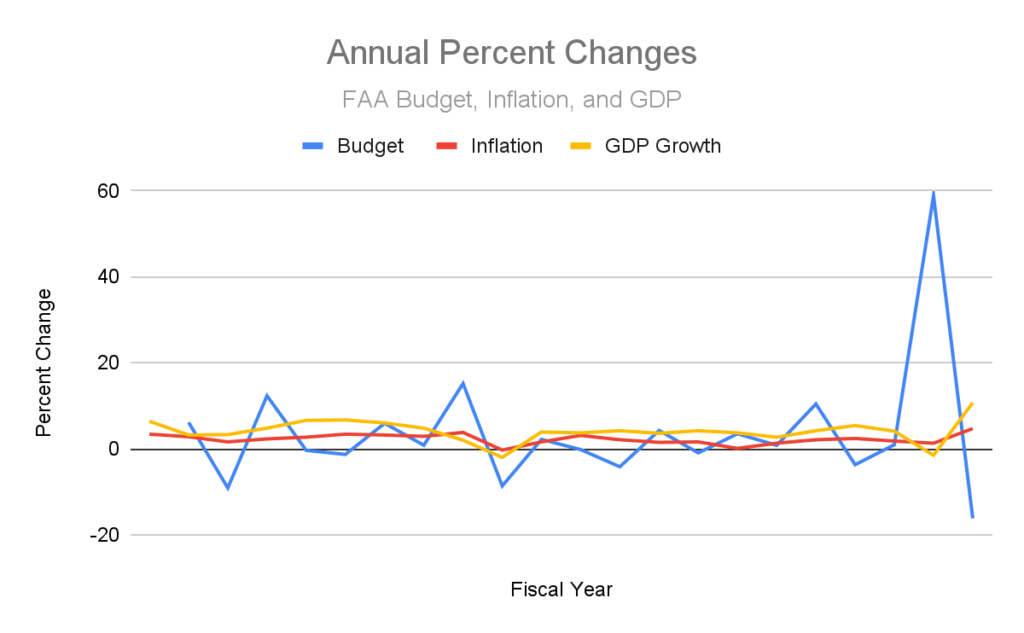

The FAA’s overall capacity has also been mostly left to languish over the past two decades, with a handful of exceptions. Most notably, as part of the fiscal stimulus designed to combat a covid-induced recession in FY 2021, the FAA’s budget increased by 59 percent over the prior year. A similar, but significantly smaller, jump occurred as part of the FY 2009 fiscal stimulus as well (an increase of 15 percent).

From FY 2001 through FY 2022, the average change in the FAA’s budget was an increase of 3.7 percent, higher than the average annual inflation rate of 2.5 percent. These averages suggest that, as a rule the FAA gained a modest amount of funding year over year. But averages can be deceiving; over this 20 year span, annual increases only outpaced inflation 8 years, while lagging inflation 12 years. More years than not, the FAA found itself with less spending power than the year before. Additionally, removing the massive FY 2021 increase, the average change falls to 0.9 percent, well below the average inflation rate, meaning that on average the FAA lost funding in real terms.

Source: Department of Transportation Budget Highlights (FY 2003-FY 2024); Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Consumer Price Index For All Urban Consumers (CPIAUCSL); Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Gross Domestic Product (GDPA)

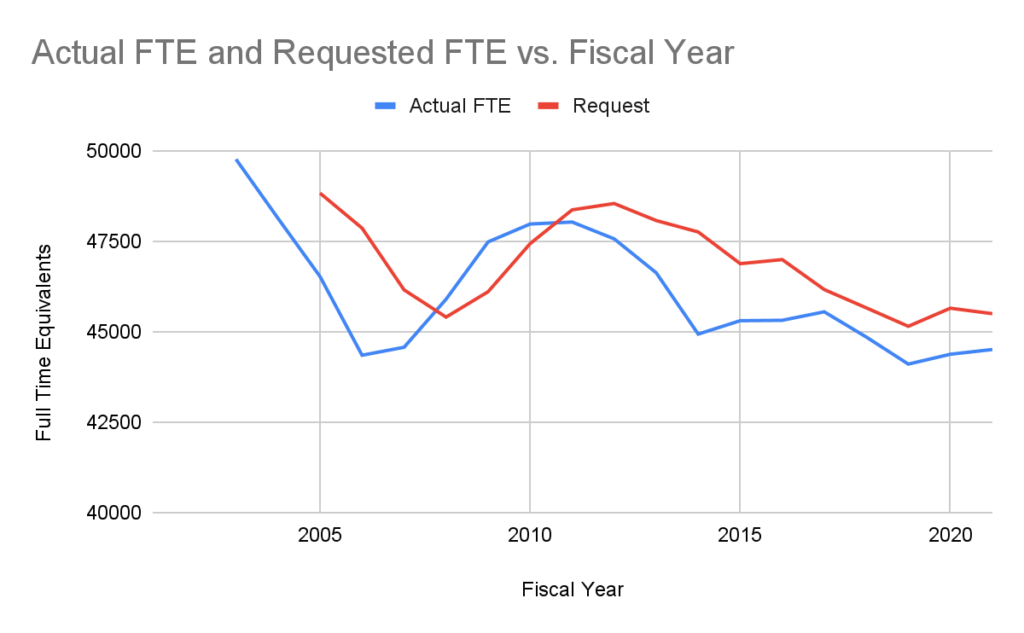

Staff levels have also stagnated at the FAA. In FY 2003, it had 49,762 full time equivalents. In FY 2022 it was down to 44,905, a loss of nearly 10 percent of its total staff.

Source: Department of Transportation Budget Highlights (FY 2003-FY 2024)

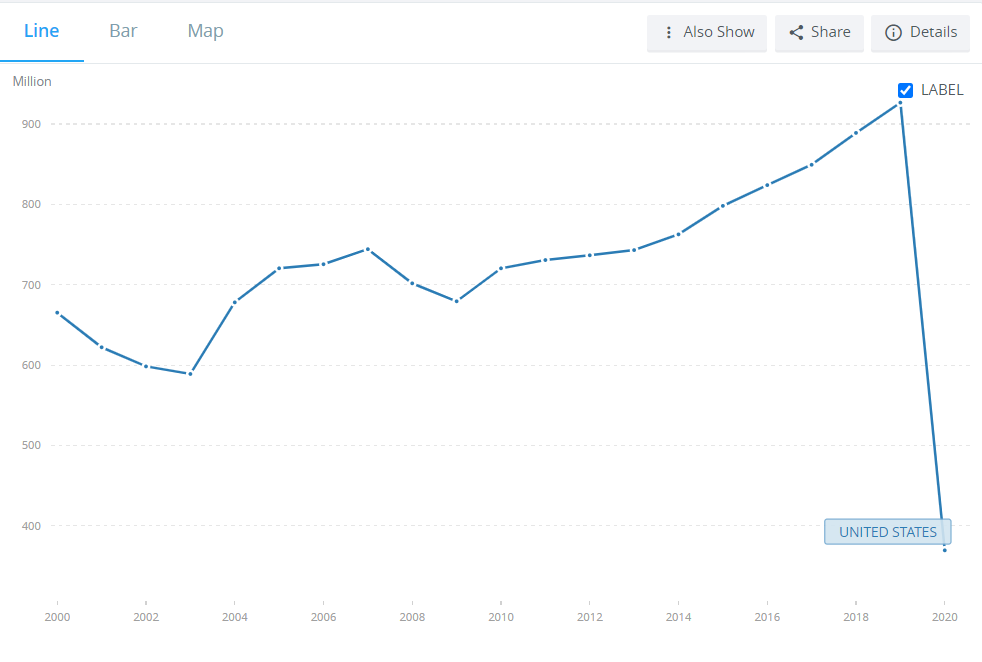

Over the same period, airline activity increased markedly. Between 2000 and 2019, the number of air passengers in the United States increased by 39.3 percent, from 665.3 million to 926.7 million. The number of departures in the United States increased by an even greater 98.1 percent, not quite doubling from 5.1 million to 10.1 million. There was a precipitous drop in 2020 due to the pandemic, with the total number of passengers dropping to 369.5 million and departures to 6.2 million. Since then, however, numbers have largely rebounded, although still short of 2019’s all-time highs.

Source: The World Bank, Air transport, passengers carried – United States

Source: The World Bank, Air transport, registered carrier departures worldwide – United States

Put all of this together and we’re left with what is an all too common story across the federal government: an FAA that has been starved of much-needed investment. It’s ludicrous that the agency tasked with regulating a growing airline industry possesses a much smaller workforce than two decades ago. Annually, there are millions more flights departing, carrying hundreds of millions more passengers left to be overseen by an FAA that hasn’t increased its staff in decades. In that time, the budget has trended upwards, but at an irregular pace. While the recent increase in funding is promising, it comes on the heels of more than a decade of only very moderate funding increases. There is a lot of ground to make up; as the airline industry has expanded, its regulators have been stretched thinner and thinner.

In FY 2003, there were 12,025 passengers for each FAA FTE. In FY 2022 there were 20,823. That’s an increase of about 67% in the proportion of passengers to FAA staff.

The FAA has also routinely been allocated less hiring authority than they have requested.

Source: Department of Transportation Budget Highlights (FY 2003-FY 2024)

This reflects a decades-long Republican effort to starve the federal executive of the resources it needs for proper oversight and regulation. There is no substitute for the sustained investment required to rebuild agencies like the FAA. One possible remedy that RDP has suggested before is expanded utilization of expedited hiring authorities, which can help to reverse the loss of staff.

A frayed FAA seriously jeopardizes public safety and corporate accountability. A shortfall in staffing will limit the ability of the FAA to perform safety inspections, investigations, protect consumers, and facilitate smooth air travel. The shortage in air traffic controllers is already resulting in reduced flight scheduling for this summer, especially through New York. Secretary Buttigieg has also complained about capacity needs. He cited rulemaking and regulation difficulties because of a lack of personnel when defending his department from criticisms around the NOTAM disaster earlier this year. He has also been vocal about the need for increased investment in air infrastructure, comparing President Biden’s budget to House Freedom Caucus calls to reduce investment and curtail funding.

The airlines and government are in agreement that the FAA needs more resources. Now it’s just the House GOP’s dysfunction that stands in the way of continuing the hard, but necessary, work of rebuilding the regulatory framework that allows Americans access to reliable and convenient travel opportunities.

Image Credit: “Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Office in Minneapolis” by Tony Webster is licensed under CC BY 2.0.