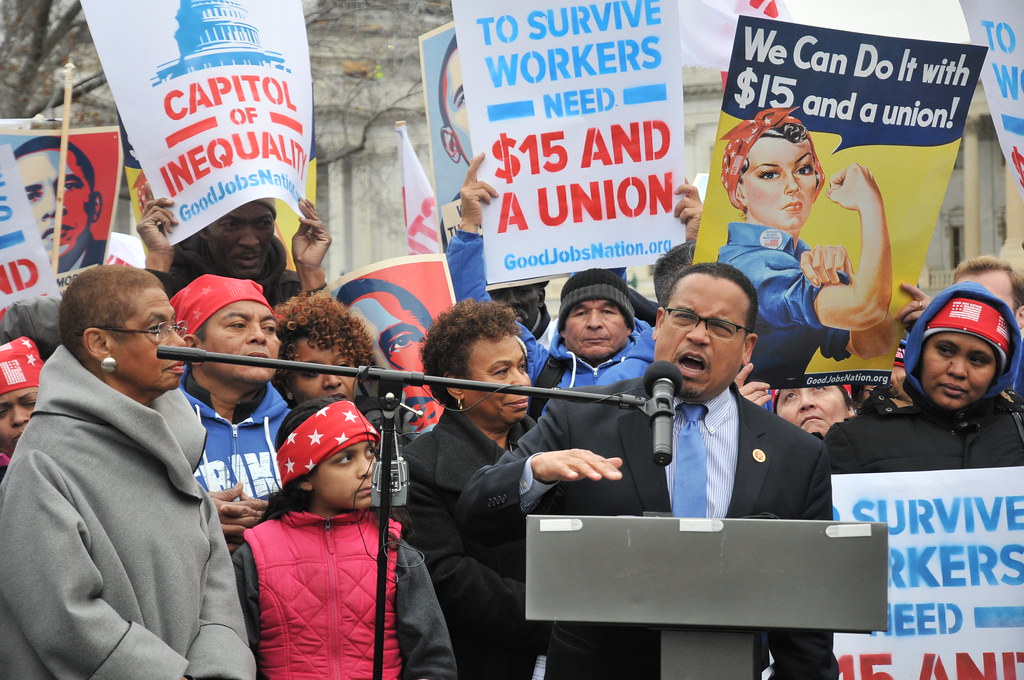

Officially speaking, the federal government employs just shy of 3.6 million people (2.2 in the civilian workforce and 1.4 in the military). In reality, however, the number of people whose paychecks originate with the federal government (through grants or service contracts) is much larger — around 12 million according to recent estimates. This workforce, and the contracts that sustain it, rarely get much attention in public discourse. Yet, the federal government’s power to set standards and direct funds through contracting is not an insignificant one. President Biden has begun to tap into those powers with directives to raise the minimum wage to $15/hour for federal contractors and institute a vaccine mandate for those same workers. These are strong first steps but they only scratch the surface of what is possible and what is needed to address the many problems that plague federal contracting. Fully harnessing that power, however, will likely require confronting a deep-seated problem: an active revolving door between the offices charged with granting and monitoring federal contracts and the companies that receive them.

The federal government’s contracting activity has created a massive commercial economy that (in 2020) was worth over $665 billion. To gain an edge securing these lucrative contracts, companies actively recruit current and former federal acquisition officials. This has created a system where there is significant personal financial motivation for current and former public officials to act in the interest of private entities. This dynamic inherently befuddles these actors’ apparent, and actual, commitment to centering the public in this work, leading to consistently bad outcomes and a general apathy regarding reform.

Constant movement between the federal government and well-paid board and consultancy positions within private industry is a long-standing, and pervasive, pattern. Out of an analysis of 30 top appointed acquisitions positions within the Trump Administration, 15 officials (50%) had a history of traveling through the revolving door, meaning that they had entered the position from the private sector, returned to the private sector following public service, or both. Of these, 11 people came from industry to the public sector, 12 went into the private sector following their public positions, and 8 did both.

These people come from across the federal agencies, and from all manner of industry affiliation. Julie Dunne, Trump’s Former Commissioner for the Federal Acquisition Service is currently a senior advisor for the Chertoff Group, a lobbying and consulting firm that employs multiple former Trump officials. Craig Leen, Trump’s Former Director for the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs in the Department of Labor, has since become a partner at BigLaw firm K&L Gates. Kevin Fahey, the former Assistant Secretary of Defense for Acquisition under Trump, came to the administration after serving as VP of Combat Vehicles and Armaments at Cypress International, a consulting firm that caters to private companies seeking to win contracts with the DoD. After his stint in public service, Fahey returned almost immediately to Cypress, this time as President and COO.

While these trends occur to a worrying degree throughout the federal government, the pattern is particularly defined from within the Department of Defense. Of the 12 DoD acquisitions officials evaluated there were 8 revolvers (66%), indicating a culture of industry entanglements that seemingly permeates the department’s acquisitions staff. This is particularly troubling given that the Department oversees almost two thirds of the federal contracting budget, amounting to over $420 billion in FY20.

Ellen Lord, for example, Trump’s former Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment and the DoD’s top acquisitions official, is particularly defining of the revolving door dynamics endemic to these positions. Prior to her nomination under the Trump Administration, Lord served as President and CEO of Textron Systems, a subsidiary of the Textron Company, an industrial manufacturing giant and defense contractor that received nearly $2 billion from the Department of Defense in FY20. Within just six months of leaving the DOD in January 2021, Lord had joined not one, but four federal contractors as either an adviser or a board member. In February, Lord joined the Chertoff Group, a “security and risk management” consulting and lobbying firm that advises clients who are seeking contracts with the U.S. Central and Africa Commands and the Air Force. Two months later, she took a position on the board of the AAR Corp., another defense contractor and aviation service provider that is currently under scrutiny for its misrepresentation of its contract fulfillment practices and the operability of Air Force machines under its purview. On average, AAR Corp’s board members earned $219,011 in FY20. In June, Lord joined Clarifai, an artificial intelligence firm, as a senior advisor and member of its Public Sector Advisory Council. Finally, in July, Lord became a member of the “strategic advisory board,” for Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) another federal contractor and one of the Pentagon’s biggest award recipients in FY20, receiving nearly $2.4 billion throughout the year. This board is currently entirely populated by former Pentagon officials, demonstrating just how valuable this experience is to corporations.

To be clear, this problem did not start with the Trump administration. Although President Obama came into office with the goal of “insourcing” more government functions, his appointees often fit neatly within the revolving door mold. Lord’s predecessor under the Obama administration was Frank Kendall III, who left his DoD role and within the year joined, among other organizations, Renaissance Strategic Advisors, Leidos, Inc., and Northrop Grumman. Renaissance Strategic Advisors is a consulting firm serving contractors in the government services and defense industries. Leidos, a rebranded offshoot of the Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), is another leading defense contractor that received more than $3.1 billion in federal funds in FY20. Northrop Grumman, similarly, is a massive global defense conglomerate that received more than $12 billion from the federal government during 2020. From just these organizations, Kendall has raked in over $2 million since 2017 ($113,750 from Renaissance, over $700,000 from Northrop, and approximately $280,000 per year from Leidos). This is not to mention the salaries and consulting fees he draws from the multiple other organizations he has since associated himself with. These sums demonstrate just how valuable acquisition officials are to the private sector, specifically because of their ability to help corporations manipulate the federal system for private and personal economic gain. In addition to purchasing these direct lines of influence, generous salaries also work in subtler ways to distort the contracting process. The promise of hefty compensation from those companies that contracting officials are charged with overseeing works to incentivize a soft, or virtually nonexistent, touch.

Kendall, notably, is back under Biden as the administration’s nominee for Secretary of the Air Force. It is deeply discouraging to us to see an exemplar of revolving door concerns rewarded despite (or because of) the sheer depth of his current entrenchment in current and potential defense contractors.

The former and current career affiliations of officials such as Lord and Kendall are significant because these actors govern the distribution of massive amounts of taxpayer money, and are simultaneously responsible for holding contractors accountable to their contracts and to the fulfillment of public interest writ large. They are charged with overseeing and guaranteeing competition in contract awards, the responsible stewardship of public funds, and for maintaining standards in the services provided. Their ability to carry out these essential responsibilities is undoubtedly threatened when they have a defined economic (and likely social as well) interest in the success of one, or multiple, contracting entities.

Relating to the Department of Defense specifically, the Project on Government Oversight and a coalition of other government watchdog groups has noted that revolving door dynamics risk “diminishing military effectiveness, [undermine] competition and performance, and [lead] to higher costs for the military and taxpayers.” Not unrelatedly, ⅓ of DoD contracts since 9/11 have gone to just five companies (Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon and Northrop Grumman), and that a lack of competition in the defense-industrial base is significantly driving up costs, degrading accountability measures, and otherwise creating too big to fail “Walmarts of War.” Of course, the current system also promotes the iniquitous pursuit of massive gains through “questionable or corrupt business practices that amount to waste, fraud, abuse, price-gouging or profiteering.” These trends are enabled by, if not actively predicated upon, the industry-driven installation of sympathetic characters to these positions of extreme power over the distribution of massive wealth.

Having industry-friendly officials overseeing contracts also jeopardizes labor rights and exacerbates the standing crisis of harmful employment practices that exists within federal contracting. Federal contracting has created a massive national market that’s a key source of employment for many communities across the country, but as the National Employment Law Project (NELP) has noted for years, many of these jobs are defined by poverty wages, little to no benefits, and labor policy violations that are difficult for workers to redress. Federal contractors are legally required to pay their workers fair wages and to comply with labor law as set forth in the Service Contract Act, but contractors have gone to great lengths to avoid this responsibility. Contractors, for example, have misrepresented the job duties and experience levels of their workforces in order to intentionally deflate workers’ wages as set by the SCA and otherwise shirked their responsibility to comply with the basic benefits policies required of them. These actions have often been met with little scrutiny from contracting officers who allow contractors to sacrifice basic employment standards for a smaller upfront price tag. This impulse ignores the fact that living wages, and strong employment safety standards, have been shown to improve the quality of contracted goods and services, and ultimately save taxpayer money.

NELP has also shown that reabsorbing many contracted positions into actual, stable, federal jobs would go even farther in reducing waste, increasing accountability, and cutting costs overall. Barring this shift in the federal landscape, however, contracting officers remain a front line defense in holding companies accountable for the quality of their goods and services and their compliance to basic (and legally required) employment policies. When these officials then have a defined interest in the contracted entity’s bottom line, this conflict of interest enables contractors’ abuse of workers, and delivery of shoddy materials, with near impunity. The government, and all of its agents, have a responsibility to defend and advocate for the public, including workers. As such, it is integrally important that these officials be scrutinized in this commitment, and all potential conflicts with it, and that steps be taken to close this pernicious revolving door once and for all.

Biden has thus far not broken with this fraught tradition of installing problematic officials to these critical offices, although many of his top acquisition positions remain without nominees. Biden’s nominee for Chief of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy, Biniam Gebre, has no discernable background in acquisition work, but has previously worked with the lobbying and consulting firms McKinsey & Co and Oliver Wyman. Indeed, he most recently worked at defense contractor and consulting firm Accenture Federal Services. Accenture received over $411 million from DoD in 2020, making it a significant beneficiary of government funds, casting doubt on Gebre’s impartiality in procurement policy making. Accenture Federal Services, the Accenture subdivision within which Gebre previously directed government consulting, also markets Accenture’s own tech solutions to various government clients and problems. This connection further implicates Gebre as a beneficiary of the private side of government contracting and clouding his apparent commitment to the public within this regulatory position. Might Gebre implement procurement policy across the government in a manner that benefits his recent, and perhaps future, colleagues?

Similarly, Biden’s appointee for the Commissioner of the Federal Acquisition Service, Sonny Hashmi, previously spearheaded Box’s Federal Services Branch. In that role Hashmi was responsible for marketing Box’s cloud computing services to federal agencies and expanding the software’s foothold in government. During his previous role with the GSA during the Obama administration Hashmi moved the agency towards a cloud-based internal system, and in this new position he plans to center further tech developments, such as reevaluating their cloud services, as key to modernizing procurement policy. This has the potential to be a major windfall for Hashmi’s former employer. Further, Andrew Hunter, Biden’s nominee for the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, is currently the Director of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank with major funding from defense contractors like Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, and Boeing, an apparent conflict of interest within the under-competed industry that is over reliant on these same manufacturers.

Biden has the opportunity, and responsibility, to reverse these trends. To start, Biden must commit himself to strengthened ethics guidelines that stop this revolving door from spinning. We have previously proposed measures to impose a two-year cooling off period prior to government service for those who are leaving regulated industries and bar them from re-entering the industry for five years after departing government. Biden must also commit to nominating to these positions people who are not mined from private sector interests and are instead firmly rooted in public service. The chronic impropriety which has defined these positions can be changed, and these standards can be challenged, but Biden must act boldly in the interest of the public to set new standards of stewardship across the federal government.