The federal government may no longer be operating under the onus of Trump-era austerity, but agencies across the federal government are still far from having the resources they need to quickly and effectively fulfill their responsibilities to the American people. For the most part, President Biden’s proposed FY 2023 budget fails to fill that gap. However, increased funding for antitrust regulation is one of the bright spots in an otherwise uninspired budget. As we have covered in the past, both the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division (ATR) saw staffing levels stagnate and budget allocations that did not keep pace with inflation or GDP growth.

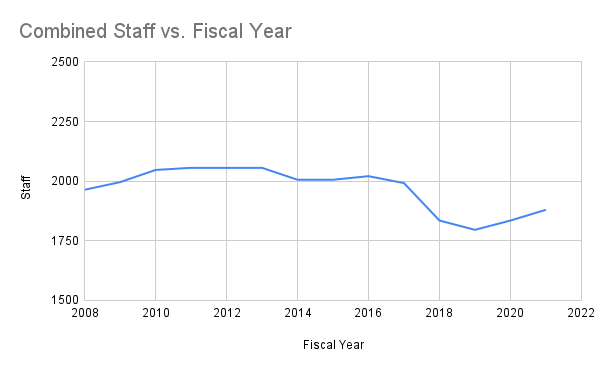

Staffing levels across the FTC and ATR declined precipitously in the early part of the Trump administration. Collectively, there were 2056 staff between the two from 2011 to 2013. That fell to a nadir of 1796 in 2019, a drop of roughly 13%. While it has rebounded since, the most recent staff numbers (in 2021) remain 9% lower than the Obama-era peak.

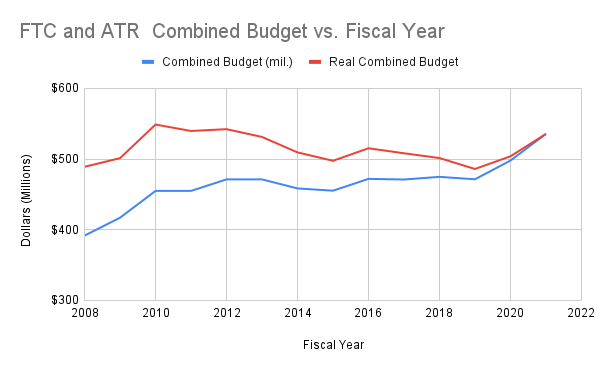

While the antitrust regulators’ budgets have consistently trended modestly upward, the actual spending power of that funding mostly declined over the past decade. After adjusting for inflation, the real combined FTC/ATR budget peaked in 2010, at $549 million in 2021 dollars. Even the recently passed FY 2022 budget, which did see more investment in regulators, only just barely returned the antitrust agencies’ funding to around 2010 levels, with a combined budget of $544 million in 2021 dollars. In short, capacity at the two primary antitrust enforcement agencies has mostly languished. However, the scope of their responsibilities has done nothing but grow.

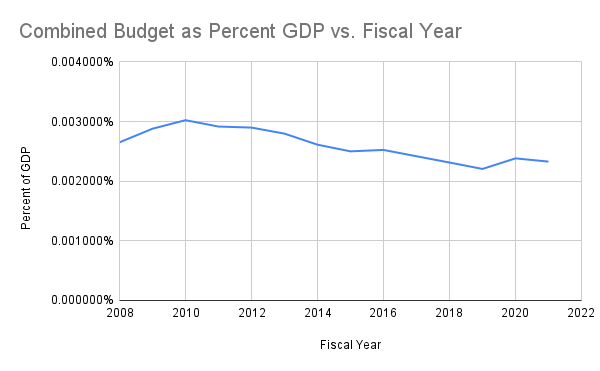

Antitrust budgets have not only failed to keep pace with inflation but also with GDP growth. It is worth emphasizing that, given the responsibility that FTC and ATR have to ensure economy-wide fair markets, the size of the economy is an important proxy for the scope of the agencies’ responsibility. During the Obama administration, the combined FTC and ATR budget consistently represented between 0.0025% and 0.003% of GDP. From 2017 to 2021, it was between 0.0022 and 0.0024, continuing the downward trend that started in 2010. While that drop may seem small on its face, at the economy-wide scale here even 0.0005% represents about $11.5 million.

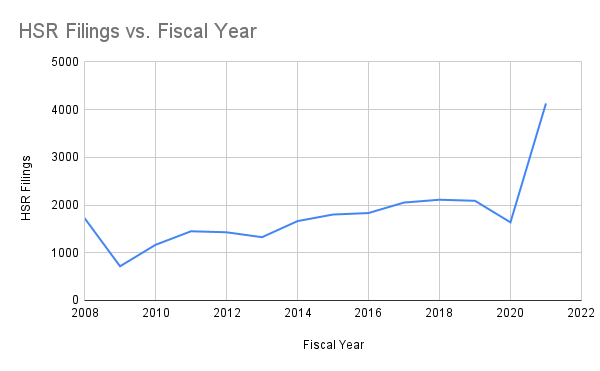

At the same time, the number of transactions reported under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act (HSR) has climbed continuously throughout the Obama, Trump and Biden administrations. According to a joint ATR/FTC press release, mergers more than doubled between 2020 and 2021. As a result, regulators are caught at the intersection of soaring responsibilities and declining capacity.

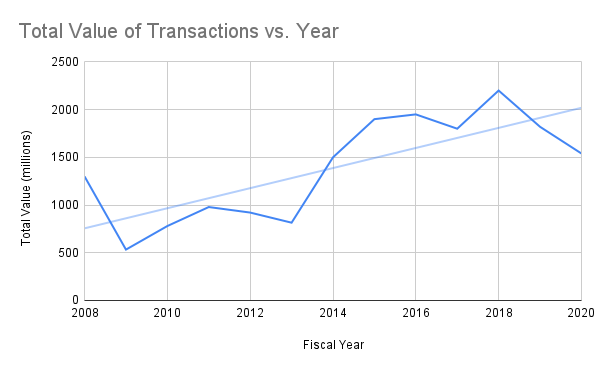

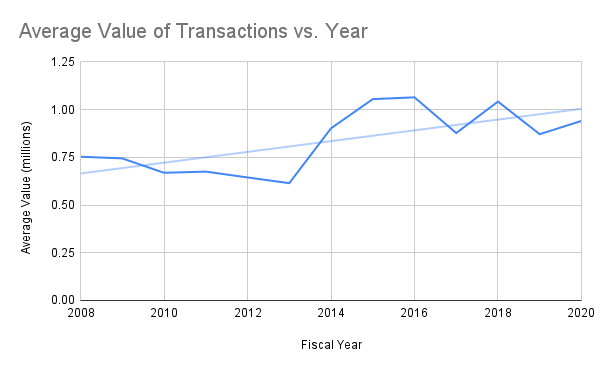

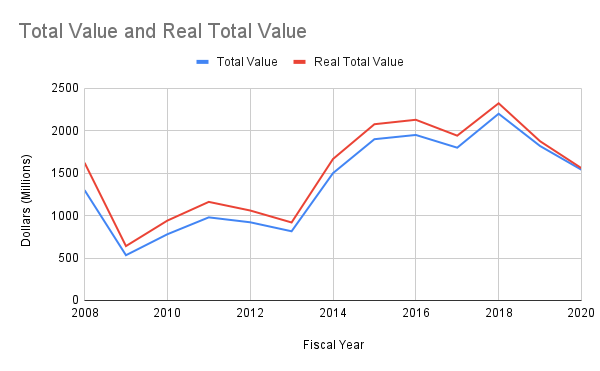

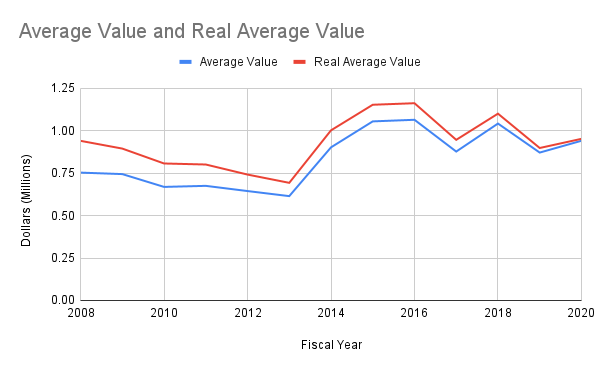

Nor does the growing quantity of HSR filings offer a complete picture of the agencies’ ballooning workload. The complexity of mergers and acquisitions has also increased, as measured using valuation as a proxy. The greater a deal’s value, the more financial relationships and accounts likely to be involved. Larger companies have more divisions, more employees, more lenders, and more distributors than smaller companies. Both the total value of all HSR filings and the average value of a filing have increased since 2008.

This measure of complexity is reliant on the quantity of money being moved, so even if these positive trends were just inflation-driven, it would still likely indicate rising levels of complexity. However, it is clear that they are not inflation-driven; the real series follow the exact same trends as the nominal series. As a result, it is apparent that the increase in valuations is being driven by larger companies and not significantly by changes in the value of their assets.

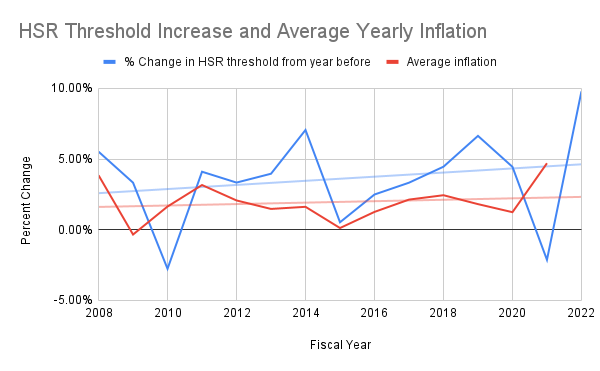

Moreover, we found that the minimum threshold for corporations reporting a transaction through HSR rose quicker than inflation for much of the time frame. Increasing the minimum size-of-transaction threshold has steadily cut out relatively small mergers from the HSR process. Thus even as the number of filings went up, HSR filings were increasingly from larger and more complex mergers.

In addition to the increasing caseload and complexity of its antitrust responsibilities, it is worth noting that the FTC has responsibilities that go well beyond combatting corporate consolidation. The FTC is also tasked with protecting consumers from fraud and deception, including false advertising and violations of privacy. The scope of that work has also been steadily growing as technology becomes more advanced and more deeply entwined with peoples’ lives.

The recent FY 2022 government funding agreement only partially addressed these shortfalls. While the combined funding for FTC/ATR did more than offset inflation, in real terms, it remains slightly below the 2010 level ($544 million compared to $549 million in 2021 dollars). Additionally, the budget remains well below what the regulators felt was necessary in 2017, when the pair jointly requested $563 million (in 2021 dollars). In the summer of 2021, Democrats had moved to give the FTC and ATR $1 billion over the next 10 years, split evenly between the two. That works out to an increase of $50 million annually. Unfortunately, as part of Democrats’ all-eggs-one-basket strategy, that funding was rolled up inside the Build Back Better legislation, which did not pan out.

Biden’s FY 2023 budget request, in contrast, does provide a meaningful bump, allocating an additional $88 million to ATR and an additional $139 million to the FTC. However, based on the White House’s release, it is unclear how much of that additional money is coming from Congress directly. One complicating factor when talking about FTC and ATR budgets is that sizable portions of both are derived from fee revenue, not congressional appropriations. When companies file an HSR notification declaring their intent to consolidate, they pay a fee, which goes towards funding both of the primary antitrust regulators. These HSR fees constitute roughly two thirds of the Antitrust Division’s budget most years, as well as a significant portion of the FTC’s. Currently, there is pending legislation – the Merger Fee Modernization Act – that changes these fee schedules so that larger firms pay significantly steeper fees. It is possible that much of Biden’s increases depend on and assume the higher HSR fee revenue that would result from passage of the act.

It is also difficult to ascertain how quickly this funding will translate into new hiring. This hiring will be critical for both regulators’ to regain their lost capacity. Unfortunately, delays in the FY 2022 federal funding process mean that the recent funding hike, while welcome and needed, is already coming quite late. Under federal law, new hires cannot be made until more funding has been made available. As such, precious time was lost to build up the federal pool of antitrust enforcers. The most recent staff levels available (FY 2021) indicate a combined number of regulators some 170 short of the 2010 level. In light of these delays, it will be all the more important that the agencies move as quickly as possible to hire new faces to support their growing missions.

Along virtually every possible metric, the antitrust agencies today are tackling a larger workload with less capacity than they were in 2010. And 2010 was hardly the golden age of antitrust enforcement. Obama largely maintained the Clinton/Bush status quo. In fact, on the ATR side, funding and staff were largely maintained at a fairly constant level throughout the quarter century prior to Trump. In other words, antitrust enforcement capacity is, by practically all measures, at its lowest point in a generation. Biden’s budget request remedies this capacity crisis on paper. Now, his administration will need to fight to see the fix implemented.

Methodological Notes

- Adjusting for inflation. We calculated real values by using this CPI data set to yearly average values, with 2021 set as the base year.

- Fiscal years vs. calendar years. For simplicity, we compared fiscal year data to the year that the fiscal year started in. Since fiscal years start in October, this resulted in n calendar year being analyzed as n+1 fiscal year. For instance, FY 2008 is paired with GDP and population data from 2007. We chose this method based on two particular merits.

- First, simplicity. This is an easy computational solution to the misalignment between data sets.

- Second, relevance. While 2007 inflation is less representative of the inflation that occurred during FY 2008 than averaged monthly CPI levels across the length of the fiscal year (October-September), it is more indicative of the economic climate at the time of decision making. Therefore, it is more representative of the information that would have been used when deciding on allocations.

- Combined staff. Combined staff is an imperfect number because of reporting differences between the FTC and ATR. While FTC reports full time employees (FTEs), since 2010 ATR only reports the number of staff positions. To calculate the combined staff, we simply summed the two figures. However, because of this mismatch, it will likely be an overestimate of FTEs and an underestimate of total employees.

Please send any questions about methodology or our findings to info[at]therevolvingdoorproject.org

Image: “U.S. Department of Justice headquarters, August 12, 2006,” by Coolcaesar is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0